Venezuela and Ukraine are the two largest contemporary forms of "man-made" migration crises, both of historic proportions. Venezuela's crisis resulted from internal political and economic implosion, while Ukraine's externally driven by Russian aggression. In just seven years, more than 20% of the Venezuelan population – six million people – have fled staggering and rapid political and economic deterioration, predominantly to neighboring South American countries. In less than one month since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, more than 3.5 million Ukrainians have fled, again predominantly to neighboring Eastern European countries in similar geographic patterns to Venezuela's. This article analyzes the key features of the two historic migration crises by scale, pace, and migrant characteristics as well as analyzes the apportionment of rights of residency and work in host countries. It finds that the startling and swifter pace of Ukraine's migration crisis is likely driving a quicker and more comprehensive set of policy responses. In contrast, it finds that the slower evolution of the Venezuelan crisis, the lower fiscal and administrative capacity in South America, coupled with a collective disbelief that the outflows could continue for so long without reversal by the Maduro government, likely explains the more disparate set of policy responses and critical underfunding of the Venezuelan crisis relative to its needs.

Introduction

The brutal Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022 has driven more than 3.5 million migrants out of Ukraine to neighboring countries in just three weeks. The continuing outflows of principally women and children is the fastest growing migration crisis the modern world has seen. It is topping all too quickly the surge of one million Syrian migrants that came to Europe in 2015-16. In South America, the political and economic implosion of Venezuela since 2015 has evolved into yet another historic migration crisis, with more than 6 million Venezuelans flooding neighboring South America over seven years.

This article looks at what is being learned from the two largest and still ongoing migration crises in the world – Venezuelans largely to South America and Ukrainians to Eastern and Western Europe. It examines these two migration crises first in terms of key features - size, pace, and disparate geographic impacts, and second in terms of the rights provided to migrants to live and work in receiving countries.

I. The Ukrainian and Venezuelan Migration Crises by Key Features: Scale, Pace, and Migrant Profiles

The 2015+ Venezuelan and 2022 Ukrainian migration crises represent distinct instances of the massive exodus of migrants in short periods with highly concentrated burdens on neighboring countries. In terms of scale, Venezuela's exodus of now six million migrants in seven years outpaces the now over 3.5 million from Ukraine (data from March 18, 2022), but perhaps not for long. By mid-April 2022 (five weeks of conflict), the numbers had grown to 4 million and were still climbing.

This section examines the distinct patterns of these large outflows in both crises and identifies the disproportionate impacts of each crisis on neighboring countries. To clarify terms, those persons fleeing conflict are understood to be refugees. Refugees are defined by the United Nations as those fleeing their country because of fear of "persecution, conflict, generalized violence or other circumstances." It is a legal definition based on a 1951 UN Convention and is embedded in the authorization for the UNHCR (United Nations High Commission for Refugees) which has played a central role in responding to the Venezuelan, Syrian and now Ukrainian crises.1 As there is a general understanding that Venezuelans and Ukrainians are compelled rather than choosing to leave their countries, there is a natural tendency to apply the term refugees to all these fleeing nationals. However, each receiving country has distinct legal processes for determining and granting asylum status and other rights to refugees once within their borders and too date only a limited number of Venezuelans have been formally designated refugees.

This article thus uses the broader term migrant to apply to all those fleeing from Ukraine and Venezuela. UNHCR, for example, reported only 49,102 Venezuelans had been recognized as refugees by March 2021.2 While there is no official international definition of migrant, the United Nations characterizes migrants as anyone who changes countries for either short or long-term residence whether legally sanctioned or not.3 Venezuelan migrants' designation as refugees and asylees has been subject to different delays in host country legal processes. With so many backlogs in asylum procedures, Brazil began granting Venezuelans presumptive, or prima facie, refugee status in 2019-20, but they have a proportionately smaller population of Venezuelans than other South American countries (see Map 1). Ukrainians fleeing war in their country are commonly referred to as refugees because of the obvious armed conflict. By using the universal term of migrant, the current article seeks to compare both migration crises on a more common basis. This permits an analysis of the rights of residency, work, and school attendance in the next section as those provided in direct response to the two crises irrespective of the individual designation of refugee or asylum status.

Contemporary Origins and Pattern of Outflows from Venezuela. While less than a decade apart, the Ukrainian and Venezuelan migration crises have quite distinct contemporary historical origins: one driven by wartime expulsion, the other by political and economic implosion. Economic deterioration was already present in 2013, when Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez died. He had progressively moved his country in a more authoritarian direction and had drained funds and investment from the state-run oil industry. His hand-picked successor Nicolas Maduro won a highly contested snap election in April of 2013 by the narrowest margins in Venezuelan history, with a recount refused to the opposition. Maduro's staggering mishandling of the economy since 2013 and misappropriation and disinvestment in the oil industry accompanied persecution of the opposition led to historic declines in economic growth, rising internal violence and the highest levels of hyperinflation ever recorded in the world – one million percent by January 2019.4

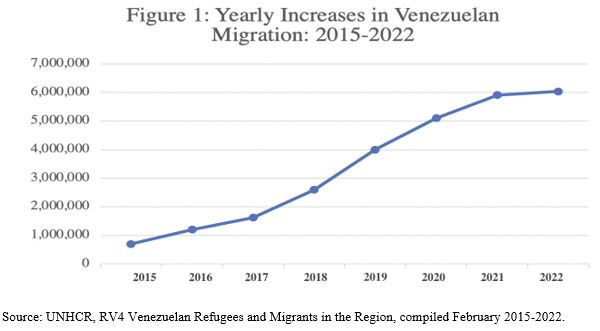

Venezuelans began fleeing in large numbers by 2015 for both economic and political reasons – political persecution, torture, sharp rises in poverty, food, and medicine shortages. The first waves, called at the time "airplane migrants," were principally those with the resources to emigrate by plane and included higher-skilled workers and professionals to both South America and the United States. In the first years of the crisis larger scale migration was held off as the Colombia-Venezuelan border, particularly the town of Cúcuta swelled with "daily migrants:'' Venezuelans crossing the border daily to buy goods and medicine unavailable on Venezuela's empty shelves. The economic downfall then became so rapid – two-thirds of the economy lost by 2019 – and the rise in poverty so great – from middle-income status to a 90% extreme poverty – that nearly all predicted that Maduro could not politically survive such dysfunction and high outflows of citizens and would be compelled to work with the opposition and reverse course. Daily migrants turned into international migrants with the largest numbers first going to nearby Colombia. Figure 1 shows the increase by year of the total number of Venezuelan migrants worldwide, climbing to a total of over six million by February 2022.

The first waves of migrants to Colombia by the end of 2018 were predominately young, moderately educated, and ready to engage in the labor force. Over 75 percent were working age, and 83 percent of those had completed at least secondary education, that is proportionately more educated than the Colombian young working age population. The biggest differences in educational attainment in the first waves were in the 25-34 age group.5 The waves of migrants coming from Venezuela after 2018, however, were poorer and walking on foot. Those crossing over the Brazilian border were predominantly indigenous peoples from the Western areas where Brazil borders with Venezuela. These later waves of migrants had lived through growing food and medicine shortages and were more severely malnourished and less educated. The COVID-19 crisis brought on even greater vulnerabilities as due to border closures and restrictions, desperate migrants turned to human smugglers to get them across illegal border crossings, making them more vulnerable to robbery, violence, and sexual exploitation. These later waves of Venezuelan migrants posed even greater demands on struggling national governments to address hunger, malnutrition, and poor health within their borders.

Contemporary Origin and Patterns of Outflows from Ukraine. The Ukrainian migration crisis was also politically created by the external aggression of Russia; there were no internal political or economic drivers motivating Ukrainians to flee. The world watched in horror as Ukraine was invaded on more than five fronts and subjected to aerial bombardment beginning on February 28, after weeks of Russian claims that they would not invade. The Ukrainian government asked all able-bodied men from 18-60 to stay and defend the country. As a result, the vast majority of Ukranian migrants are reported to be women, children, elderly men and the disabled.

Distinct from Venezuela's rolling and ever swelling crisis over seven years, Ukrainians made last minute decisions to leave their country, fleeing the unprovoked bombardment of Ukraine and invasion of Russian troops. The Ukrainian government continues to compassionately seek safe corridors and organize transportation for its citizens to leave. The International Rescue Committee (IRC) reported that over two-thirds of migrants with whom they had come into contact were women and children and that, due to the characteristics of this population, they were particularly worried about gender-based violence as well as trafficking and exploitation of children.

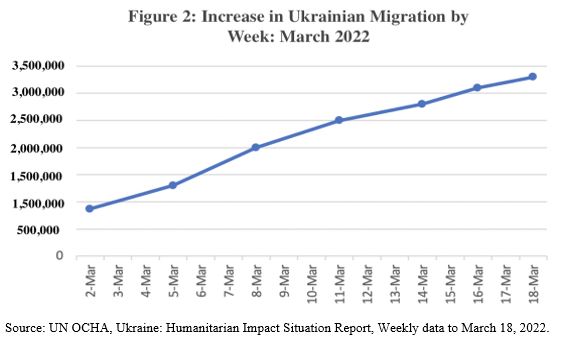

Figure 2 below shows the weekly climb of migration outflows during March 2022 from under one million to 3.5 million. These figures also include a currently unknown number of third-party nationals (TPN), non-Ukrainians who had been living in Ukraine and driven out by the Russian invasion. Estimates are of course rolling and understandably speculative as they are based on daily reports from multiple sources, including border crossings, reception centers and international and non-profit agencies. Nonetheless, the slopes of Figures 1 and 2 look remarkably similar except the Ukrainian outflows are measured in weeks and the Venezuelan outflows in years.

Figure 2 does not contain the additional millions who are internally displaced within Ukraine. As of March 18, the UNHCR estimated that 1.9 million people were internally displaced within Ukraine.6 They also indicated that millions more Ukrainians were stranded in war-affected areas, unwilling or unable to leave due to security risks and blocked infrastructure. Just how many internal migrants will become international migrants is uncertain. A March 8 survey by the International Rescue Committee found that 21% of those stranded within Ukraine in the areas they served had no intention of trying to go further.7 Internal displacement was not a factor in the Venezuelan migration crisis except for the estimated 60,000 - 100,000 Venezuelans who had lost housing and tried to return to Venezuela between March and September 2020 only to be quarantined in squalid shelters and prevented from returning to their Venezuelan homes for weeks.8

It is too early in the Ukrainian migration crisis to have skill profiles and assessments done for Ukrainians refugees seeking to resettle in Eastern and Western Europe. However, knowing the high proportion of female migrants in the current pool, we can draw on recent labor force data from the International Labor Organization (ILO) and World Bank for the Ukrainian nation as a whole to approximate some key characteristics of the female-dominated labor pool. Education levels of females in Ukraine is on average remarkably high and significantly higher for females than males. In 2020, 47% of men and 63% of women had some tertiary (university-level) education. The 2020 labor force participation rate for women, at 48% is in comparison relatively low compared both with other European countries with high education levels, signaling a reduced percentage of highly-educated women with current employment experience.9 Those women who were working in Ukraine in 2020 worked disproportionately – 73% – in the services sector, while women comprised only 13% of both the industrial and agricultural sectors.10

The Migration Crises by Geographic Impacts and Migrant Destination

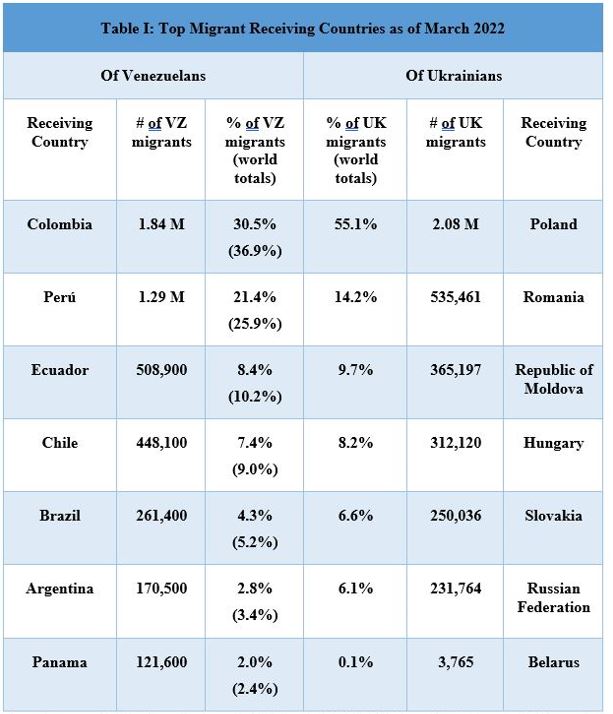

While the migrant outflows from each of these crises differed in speed, pace, and profile of migrants, each demonstrates a clear similarity in the disproportionate impacts on neighboring countries. Table 1 combines the most recent geographic distribution of both Venezuelan and Ukrainian migrants in each country's top seven receiving countries. In both migration crises, the top seven recipient countries are all neighboring countries within the same region. Colombia and Perú combined host 52% of all Venezuelan migrants, while similarly, Poland currently hosts 55% of all Ukrainians.

To compare the Venezuelan and Ukrainian crises using common UNHCR statistics, the percentages represent totals for all Venezuelan migrants per country as a percent of total Venezuelan migrants in the world, and likewise all Ukrainian migrants as a percent of world totals. For the Latin American receiving countries, a regional percentage is given in parenthesis, specifically the percentage of Venezuelan migrants as a total in South America. These additional figures show the relative disproportionate weight that Colombia and Perú bear within South America.

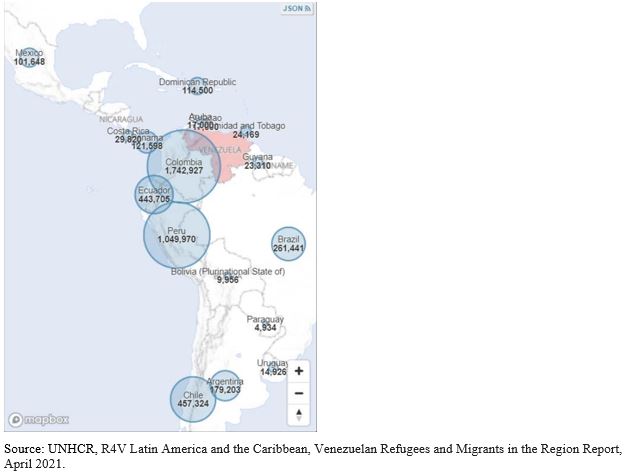

Venezuela. Map 1 below shows -- by size of circle -- the proportions of Venezuelan migrant settlement in neighboring South America. Even as outmigration rose from one million early in the crisis (2015) to six million by 2022, Perú and Colombia remained the top hosting countries of Venezuelan migrants every year. Chile has more recently become the third South American host country attracting largely poorer Venezuelans migrating on foot through Colombia and Perú from 2018 onwards.

Map 1: Geographic Concentration of Venezuelan Migrants in South America

Colombia's role as the top recipient of Venezuelan migrants can be linked both to geography and history. Colombia shares a 1,378-mile border with Venezuela, with both official border crossings and hundreds of miles of dense jungle where non-official crossings occur. Colombians remember well their shared history of migration with Venezuela. Venezuela opened its doors to Colombians migrating during its long civil war with the FARC and ELN rebel forces which only officially ended in 2016; Colombians also migrated to Venezuela for jobs during its oil boom years. Colombians and Venezuelans now share families across borders; Colombian President Ivan Duque has called the Venezuelans "our brothers."

In the early years of the Maduro administration, Venezuelan migration was highly concentrated in border towns and the capital city of Bogotá but has, over time, distributed throughout the country in smaller towns and agricultural areas as well. Venezuelan migrants to Perú are instead still highly concentrated in the capital city of Lima.

Source: Data compiled by the authors from the following: UNHCR, RV4 Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants in the Region Report, as of February 2022; UN OCHA, Ukraine: Humanitarian Impact Situation Report, as of 3:00 p.m.

(EET), 20 March 2022. Figures are for only the top seven receiving countries, not all Ukrainian and Venezuelan migrants worldwide.

(%) Share of Total Migrants in Latin America and the Caribbean region.

Proximity remains the principal driver of the destination of Venezuelan migrants. While South America is the most dominant sub-region, the Latin American and Caribbean region overall receives the vast majority of Venezuelan migrants. Of the estimated 6.04 million Venezuelan migrants in the world in February 2022, more than 4.99 (82%) million are hosted in the Latin American and Caribbean region.11 This geographic burden is particularly noteworthy because of the Latin American and Caribbean region's poorer economic conditions and concentration of informal, low-paid work.

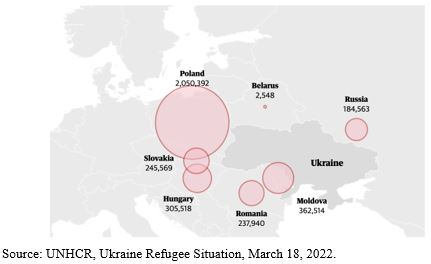

Ukraine. Map 2 provides the proportionate flows of Ukrainian migrants to neighboring destinations in the first month of the crisis (March 2022). In their proportions, these flows show remarkable similarities with Venezuela in the high concentration on key bordering neighbors. Poland, a country of approximately 37.8 million people, took in more than two million Ukrainians by late March, although some may be later transported further to other Western European nations. Poland, like Colombia, serves as the lead nation for receiving Ukrainian refugees and migrants. There were already one million Ukrainians living in Poland, so a portion of the refugees can be housed with families. Their languages are similar, and they share a "tangled" history in the words of the Economist.12

Map 2: Geographic Concentration of Ukraine Migrants as of March 2022 in E. Europe

After Poland, the next group of top receiving countries are smaller Eastern European neighbors, each bearing a relatively similar proportion of Ukrainian refugees and migrants: Romania (14.2%), Republic of Moldova (9.7%), and Hungary (8.2%) (Table 1). As a percentage of their current national population, Poland is absorbing a particularly high percentage of Ukrainians – 5.4%, with Romanian absorbing what constitutes 2.7% of its 19.2 million population. The high initial geographic concentration in the case of Ukraine reflects the "wartime" evacuation nature of the crisis. International organizations and national governments have set up receiving centers for fleeing Ukrainian in key border countries. The Ukrainian government bravely organized transportation, mainly by bus and train, to get Ukrainians out as quickly as possible to safety in bordering countries.

The Venezuelan migrant crisis has remained highly regionally concentrated in the same South American receiving countries through all seven years of the crisis. While it is too early to make the same predictions for the Ukrainian crisis, there are clear signals that Ukrainian refugees and migrants will have more freedom of movement within the European Union, other Western European countries and even Japan to resettle to third countries after first transiting to the top receiving countries of Eastern Europe. The European Union and Western European countries are providing more automatic rights of residency as well as work. The Schengen area of the European Union permits free movement across its borders and countries such as Germany are beginning to provide transportation to Ukrainian refugees from border countries. This ability to move more systematically and easily away from border countries was not offered in the case of the slower-moving Venezuelan crisis. The following section analyzes the different rights of residency, work and international support for the two migrating populations.

II. Rights of Residency, Work and Support for Venezuelan and Ukrainian Migrants

This section examines how and whether Venezuelan and Ukrainian migrants are provided the legal right to live and work after fleeing their native countries. It alas well as rights for their children to attend school in receiving host countries. It finds that the swifter understanding of Ukraine as an explosive crisis of historic proportions is likely driving a quicker and more comprehensive set of policy responses to enable Ukrainians to live and work outside of Ukraine more easily in the midst of war in their country. South America, in contrast, has become a web of very different processes, leaving more than half of Venezuelan migrants in the region without legal status by March 2021. A new initiative by the Colombian government, however, offers the most extensive protections yet to Venezuelan migrants living in their country.

Access and Rights of Residency and Work

For Venezuelan Migrants. As the first waves of migrants fled Venezuela, the South American neighboring nations showed relative openness to receiving Venezuelans,13 particularly given their own economic struggles and weak institutional capacity. However, as the pace of Venezuelan migration accelerated new laws and procedures enacted in South American countries and poor labor markets couldn't keep pace with the unexpected high volumes. Depending on which Latin American country a Venezuelan would enter, transit through, or seek semi-permanent residency, Venezuelans faced lengthy bureaucratic processes and uncertain outcomes. Access to basic health and social services for migrants was very limited except for emergency services. As a result, international donors began creating migrant-specific additional programs to serve social service needs, but coverage was understandably spotty. The most cumbersome legal processes were receiving the right to work in formal sector employment and the right of residency. No two countries had similar processes. Nearly all Latin American and Caribbean countries permitted Venezuelan children to enroll in school, although many schools were overburdened with little capacity to absorb more school children. Asylum processes were particularly slow, and thus the focus became on mass "regularization" campaigns to "legalize" Venezuelan migrants who were already living in their countries but without explicit authorization (e.g., valid papers) for residency and work.

The enacted regularization procedures turned out to be poorly adapted to mass migration. Many national permit processes had selective eligibility requirements and short time frames, requiring frequent renewals. Work permits could be a separate process from residency, also with different time frames for renewals. Many Venezuelan migrants didn't have the knowledge, time or even the qualifying documents to apply. Perú, Colombia, Chile and Brazil had instituted their own types of temporary residency visas with special procedures. As characterized by the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) et al. in their 2020 study Labyrinths of Documents: "The exponential increase in Venezuelan migration in the last five years has stressed the standards and practices of migration and asylum systems and the countries of the region have implemented diverse and differing systems in reaction."14

By late 2018-19, three of the six top receiving South American countries were backtracking on inclusionary policies for Venezuelan migrants. Ecuador, Chile, and Perú were making it more difficult to obtain legal status, likely believing this would discourage more immigration and divert Venezuelans to other nations. Ecuador and Perú required passports with visas for official entry even though they were aware that the Maduro government was no longer renewing passports for its citizens. By all accounts, the 2018-19 restrictions in these countries led to more Venezuelans crossing "illegally" at more dangerous, non-official borders to avoid being turned back, making more migration in the region "irregular."

Special regularization processes are currently the dominant way Venezuelans are to acquire the national "papers" needed to have the right to live, secure decent housing, and work in the formal sector in South American countries. Year by year, as these processes became overwhelmed, more and more Venezuelans were living in South America under irregular status, highly concentrated in doing precarious, informal work.15 As late as March 2021, UNHCR's data from national governments found that only 2.2 million Venezuelans had received some form of regularization status. However, this figure included duplications and expired permits, so the current number of regularized Venezuelan migrants is both much lower and not precisely known. Asylum numbers are also low for Venezuelans—only 49,100 Venezuelans received asylum in the top six South American host nations and over 600,000 still have asylum claims pending.16 Regularization for Venezuelan migrants in South America has turned out to be a patchwork of different qualifying regulations and bureaucratic procedures that have worked both slowly and for far too few. This mix of legal statuses has infinitely complicated the delivery of services to migrants, as migrants without the proper papers qualify for so few nationally run services.17 South America has yet another assortment of donor-driven food and medical programs, initiatives of local governments with large migrant populations, non-governmental organizations, and national governments, all trying to patch up and support migrant needs on too small of a scale. The March 2021 figures reveal that less than a third of five million Venezuelan migrants in the top South American host countries had qualified for time-limited rights for residency and work.

Colombia, however, has offered a way forward out of the patchwork of permits. As the largest receiving country of Venezuelan migrants, Colombia has demonstrated relatively more generous processes to grant temporary residency and formal work status. It had previously created a separate work visa program, the PEP (in Spanish the Permiso Especial de Permanencia) in 2019. The PEP enabled Venezuelans to work legally in Colombia for from 90 days up to two years and allowed for two-year renewals. However, the PEP too was highly bureaucratic, and employers shied away from hiring Venezuelans for formal jobs, both for the scarcity of formal work and for the uncertainty that the Venezuelan PEP's would be renewed.18

However, in March 2021, Colombia President Ivan Duque made a stunningly generous announcement: Colombia would create a plan to give qualifying Venezuelans, ten years of legal residency, access to all services, and the ability to work without restrictions. Colombia's new proposed Temporary Protective Status (known as "TPS") for Venezuelan migrants has been called by international leaders "historic" and "one of the most important humanitarian gestures in decades."19

Colombia's TPS is far more generous than anything any country has yet provided to Venezuelan migrants. TPS will not be granted automatically nor under a prima facie assessment. There is yet another new bureaucratic process that was initiated in May 2021 to obtain TPS. Migrants must register with a new online format, then submit biometric data, have their case reviewed, then have their document printed and sent to them. Migración Colombia (the Colombian ministry managing migration policy) reported that 1.8 million Venezuelan migrants had registered with the online system as of January 31, 2022.20 In the first eight months, more than 700,000 TPSs have been approved, and 531,431 Venezuelans have physically received their TPS documents.21 Those with the PEP work permit are being encouraged to transition to the new TPS. While the Colombian Ministry of Foreign Affairs still has the right to extend or limit the 10-year TPS at any time, the extension of TPS to half a million Venezuelans in its first year is a major leap forward. The ten year time period reduces bureaucratic burdens, but most importantly advances local integration of migrants, enabling them to live with less precarious housing, more stable employment, and have access to national social services. This reduces the need for separate donor-financed services for migrants who have no access to health care or stable housing, a lesson to be brought forward to the growing Ukrainian crisis.

For Ukrainian Migrants. On March 3rd, only eight days after the first Russian bombs were shot into Ukraine, the European Union had agreed to a "Temporary Protection Directive" (TPD) that provided all those holders of a Ukrainian passport with the common standard of up to three years of residency and the right to work in the European Union. This is the first time the European Union has used the TPD since it was created 20 years ago in response to the refugees coming from the breakup of Yugoslavia.22 The European Union's rapid response is uniquely based on a universal European-wide standard, relatively long periods of residency, work and schooling rights and access to services. This combination of rights for migration management is unprecedented in the speed of provision so early in the crisis, the scope of its application across distinct national borders, and the focus on reducing administrative burdens.

Now, each of the EU-receiving countries is moving forward under the guidance of the TPD with specific national procedures and eligibility for temporary protection, but eligibility must be immediate. Germany is exempting all displaced persons from Ukraine (including third party nationals who were residents in Ukraine) from the requirement to hold a residence permit until May 23, 2023. This means that they can enter and live in Germany now and have a full year to apply for temporary residence. Meanwhile, they are also eligible for medical and social services. In addition to temporary residence, Slovakia is providing a stipend to Slovak families that take in Ukrainian migrants.23 Poland's current plan is to issue temporary protection for one year from March 4, 2022, with the possibility of further extension for six months. Poland also adopted a related, complementary bill that allows Ukrainian citizens, their spouses, children, and close family members of Pole Card holders, who left Ukraine even before February 24, 2022, to stay and work in Poland with simplified administrative formalities, as long as they had come directly to Poland. . A particular advantage in Ukrainian resettlement will be in helping them travel to Ukrainian families already in Europe. A 2018 survey by the UN International Organization of Migration (IOM) found that one-quarter of Ukrainians reported they have or had a family member that had previously worked abroad.24

Many non-EU countries such as Norway, Sweden and Switzerland are enacting protocols following the TPD of the EU. One notable exception is the United Kingdom (UK). The UK still requires Ukrainian nationals to apply for a visa before entering Britain. They enacted an online visa application and required Ukrainians to submit biometric data. The Foreign Office was openly discouraging Ukrainians from showing up at the British Consular office in Calais, France to apply in person for a visa, sending them away and telling them to apply online. The Manchester Guardian termed it "a marginal simplification of the web of bureaucracy that Ukrainians attempting to take refuge in the UK face."25 This criticism of the British approach echoes the problems that resulted from more heavily bureaucratic approaches utilized in all South America to slow down the ability of many refugees to integrate into receiving countries, leaving migrants facing greater social and labor market marginalization.

Within the EU, as well as around the world, the response to the Ukrainian crisis has been predominantly generous and ground-breaking. The most difficult work though lies ahead in the implementation phase which must continue to adjust to a war in Ukraine that may go in unpredictable directions. Reliance on the current capacity of schools and stock of low-cost housing in Europe, for example, will likely not be sufficient in the medium-term.

Perspectives on Learning from Crises

Mass migration crises on the scale of Venezuela and now Ukraine likely will not be the last. By analyzing the key attributes of both crises and how and whether rights of residency and work are provided to migrants, this article sought to aid collective learning. Learning that not only applies to these ongoing crises but also to the currently unimaginable future ones.

While of distinctly different origins, Venezuela and Ukraine share the common characteristic of disproportionate impact on their geographic neighbors. In both cases, there are clearly "lead" countries—Poland and Colombia—both in terms of receiving the largest share of migrants and in terms of national policies to respond to the crisis. Poland received more than two million migrants within the month of March 2020 alone, while Colombia more than two million over the span of seven years.

Due to their different origins, the profiles of fleeing migrants were quite different, offering distinct types of integration challenges. In the case of Venezuela, the relatively younger and more educated left in the first waves, with the much poorer and lesser-skilled dominating the larger post-2018 waves. Fleeing war, the current wave of Ukrainian migrants are predominantly women, children, and elderly men. Women from Ukraine on average have proportionately higher levels of university education and proportionately less work experience, signaling different challenges for labor market integration than those posed to South America.

South America's web of permits, applications, and reapplications reflects its lower economic levels, its poorer fiscal and administrative capacity, and the slower escalation of outflows. It also likely reflects collective wishful thinking that the outflows would soon slow—won't the Venezuelan government have to address the economic and political collapse driving migration? Colombia's newest TPS initiative for Venezuelans is a remarkable exception for a developing receiving country, but further widens the differences in policies, support, and rights for Venezuelans in South America.

While not likely directly learning from the Venezuelan crisis, the European Union can see a mass migration crisis coming clearer than South America did. With its Temporary Protective Directive, the European Union is poised to overcome one of the biggest weaknesses of the international and regional approach to the Venezuelan crisis: the devolution of residency and work permission into a confusing set of short-term permits that were difficult to deliver. Holding back legal residency, work permits, and services has not discouraged migration into South America, but rather has created defacto barrios of millions of migrants living in "irregular status" which has resulted in even greater demands on struggling national governments to address increased poverty, hunger, and malnutrition within their borders.

Europe should stay attentive to avoid the establishment of European barrios filled with Ukrainians waiting to access services, unable to seek work or attain semi-permanent housing. The promise of the TPD must be secured through the painstaking work of national government implementation strategies.

No bureaucratic timeline will be able to predict when Ukrainians can safely return home. Shortened periods of eligibility for residency and work by individual EU states will not be decisive in discouraging where migrants go, as it wasn't in the case of the more restrictive policies of Chile, Ecuador, and Perú for Venezuelans. Best practices in migrant resettlement and placement tells us that dispersal of the population can significantly increase employment outcomes.26 A key missed lesson from the Venezuelan crisis to the current Ukrainian-receiving countries is the advantage in getting migrants and refugees as quickly as possible into secure housing and employment. Better migration management, not restrictions on residency and work, is the more effective way of reducing burdens on host countries. The objective of migration management in cases of mass migration would best be to put more and more migrants into the position of being able to take care of their families and themselves while they await a better future in their homeland.

Footnotes

Download here.

Footnotes

Download footnotes here.