Since 2014, irregular migration from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras to Mexico and the United States has steadily increased. As a result, the respective governments of each country have struggled to reduce irregular migration and guarantee international refugee law in the process. This article frames the persistence of irregular migration in the context of a dearth of accessible regular migration pathways. It then examines the H-2B nonagricultural seasonal visa program in the United States, which the Biden administration has posited will supplant irregular migration from the region through nationality-specific allocations. The viability of employment-based visas as an alternative to irregular migration is discussed. We conclude with a series of recommendations for the governments in countries of origin and destination to channel irregular movement into regular pathways in the short- and medium-term.

Introduction

Irregular migration northward from Central America has grown steadily since 2014. A particularly high level of encounters at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2021 has made clear that the United States and its regional partners face a long-term challenge to promote orderly and regulated migration in the region.1 While providing the possibility of asylum in the United States and Mexico is vital,2 other regular channels such as employment-based visas are rarely considered as an alternative to irregular migration, despite evidence that motivations for emigration often include both security and economic factors.3 Demographic trends indicate that people will likely continue to emigrate from Central America until roughly 2050. Providing safe and transparent legal pathways could be critical to reduce unauthorized migration to the United States and establish regulated migration processes as the norm.

The Biden administration has formally recognized the expansion of the H-2B nonagricultural seasonal visa program as a means to meet these objectives in the short- to medium-term.5 The visa offers an opportunity for Salvadoran, Guatemalan, and Honduran nationals, among others, to legally work in the United States for limited periods of time, with the option to renew their visa conditional on compliance. This temporary visa meets employer demand and creates potential for returns on development while visa holders are in their country of origin during the off-season.

Despite the H-2B program's promise in helping to manage migration from Central America, some issues may impact its efficacy in reaching these goals. Assessing the viability of regular pathways to supplant irregular migration requires theoretical and practical evaluation of the regular pathways being considered. Theoretically, there is a large gap in the literature surrounding the impact of regular migration on irregular migration, and no causal evaluation of this relationship in the North American context exists to date. A causal study would clarify the relationship between regular and irregular migration specifically in the Northern Triangle and properly assess whether the H-2B initiative has met its objectives.

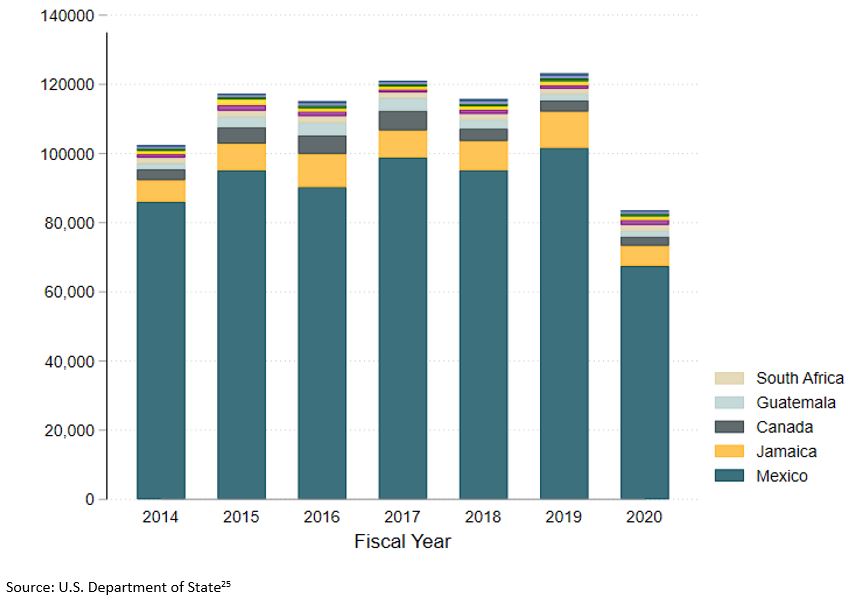

Practically, several challenges persist that limit the implementation of the H-2B program. Historically, U.S. employers have hired workers predominantly from Mexico through this program. Only 4.71% of H-2B visa holders between 2014 and 2020 were from El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras. As such, logistical and financial costs will be incurred as the H-2B program expands in the three Northern Triangle countries. Recruiters and employers who exploit migrant workers during the recruitment and employment processes present threats to these programs as well. Finally, the prospect that migrants with H-2B visas may fail to comply with its requirement to return to their country of origin could undermine the program's efficacy in meeting these broader goals.

This article provides recommendations6 to make the H-2B visa a more effective tool for managing irregular migration from Central America. As we argue, the H-2B program and other regulated employment-based programs are important instruments in developing a migration management framework in the region.7 In order to expand the H-2B program's presence in Central America, U.S. policymakers must advance domestic-focused measures as well as regional cooperation with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. These measures will not entirely curtail irregular migration to the U.S.-Mexico border. Yet temporary work visas offer one pathway to mitigate current and future irregular migration in the region.

To this end, we review the historical trends in regular and irregular migration in North America to frame the discussion of the H-2B visa program in the United States. We discuss the existing literature on the relationship between regular and irregular migration. We then explore the practical challenges that remain for successful substitution of regular pathways for those that are irregular. We conclude with a series of recommendations that U.S. policymakers can incorporate within the U.S. immigration system and in conjunction with the three countries to put forth regular pathways as effective tools to reduce irregular migration from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras.

Migration Trends in North America since 2014

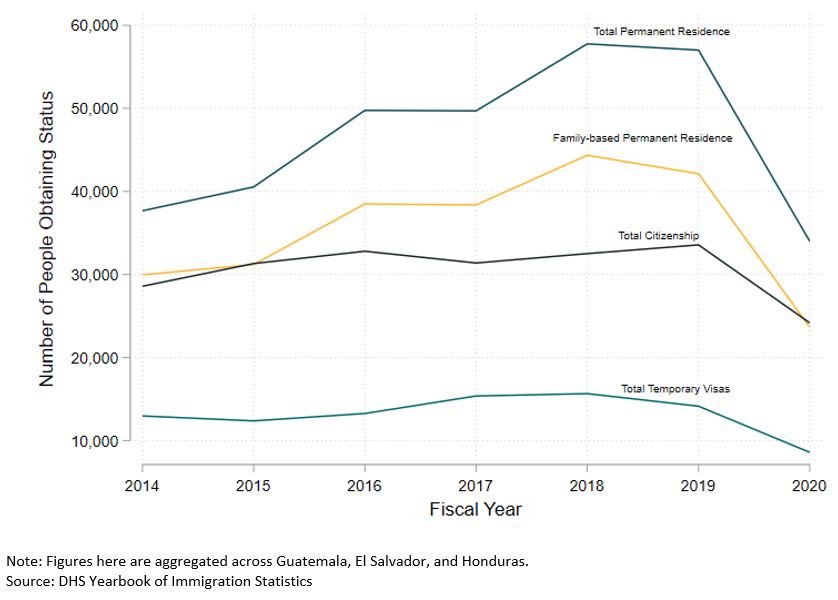

Aside from interruptions to global mobility in 2020, migration from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras has been increasing to Mexico and the United States through both regular and irregular channels. The most common U.S. migration pathways that individuals pursue are family-based, given the large Central American diaspora that has lived in the United States for decades.8 This has allowed many people to thereafter pursue U.S. citizenship. However, temporary visas for tourism, business, or employment remain the least common visa issued to those from Guatemala, El Salvador, or Honduras. A majority of applications for tourist visas, for example, get denied in each of the three countries.9

Figure 1. Regular Migration from the Northern Triangle to the United States, 2014 - 2020

This trend can also be observed in Mexico as more people from the Northern Triangle countries have settled there. Between 2015 and 2020, the share of Guatemalans among the immigrant population in Mexico increased from 4% to 5% and the share of Honduran immigrants increased from 1% to 3%. Additionally, Mexico's Commission for Refugee Assistance (COMAR) received 70,000 asylum requests in 2019, more than double the 30,000 requests in 2018. Hondurans have filed the majority of asylum applications in Mexico over the last five years.10

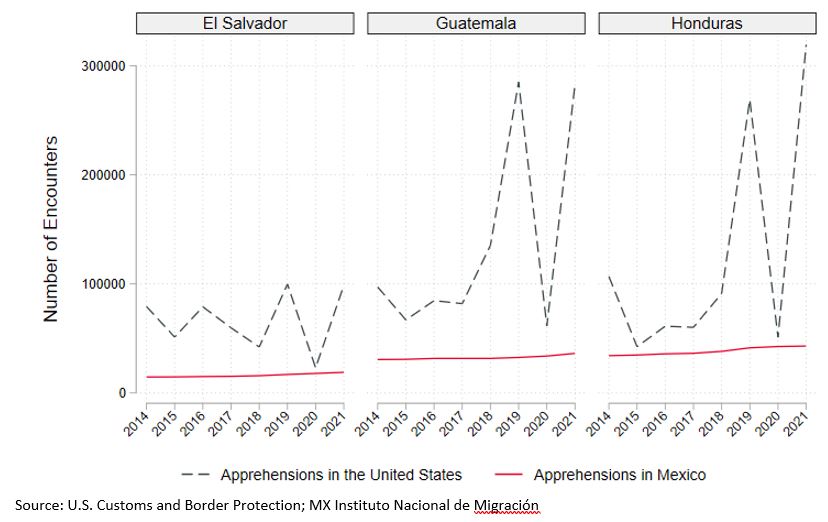

However, relative to regular pathways, irregular pathways remain much more accessible for people to reach the United States from the Northern Triangle. As a result of extensive trafficking networks and high visa denial rates at U.S. Consulates in the region, many people migrate without documentation each year.11 The exact number of people who pursue irregular migration to Mexico and the United States each year is elusive, given the informal nature of such movements; however, the number of encounters at the U.S. Southern border alludes to the predominance of unregulated pathways.

Figure 2. Irregular Migration from the Northern Triangle to the United States and Mexico, 2014 - 2020

Irregular migration substantially increased during 2021. This may be a result of a confluence of factors. The Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP), which require asylum seekers to remain in Mexico for the duration of their US immigration proceedings, and the Title 42 policy which, citing COVID-19 health precautions, permits automatic expulsion of most adults, have been identified as potential reasons for the increase in apprehensions during 2021.12 Other driving factors include increased levels of violence, worsening economic conditions, and decreased access to in-person education in countries of origin.13

The number of encounters may be a misleading proxy for the number of people migrating irregularly in this instance, however, due to Title 42. Under this policy, people who enter the United States without documentation can be automatically expelled without formal deportation processing. This results in shorter processing times and no documentation of unlawful entry, both of which allow people to reenter multiple times. According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection, "prior to the pandemic, about one in eight border encounters involved a person previously encountered during the prior year. However, since CBP began expelling noncitizens under the CDC's Title 42 public health order to limit the spread of COVID-19, the repeat encounter rate jumped to more than one in three encounters, including almost half of single adult encounters."14 Thus, the number of total encounters at the U.S. Southern border overstates the number of unique people attempting to cross.

Despite the incompleteness of apprehension data of immigrants detained at the border by U.S. Border Patrol, both the United States and Mexico recognize increased levels of irregular migration across their borders. Previous initiatives between the two countries, such as the Working Group on Migration and Consular Affairs of the Mexico-U.S. Binational Commission in 1997, the Repatriation Strategy and Policy Executive Coordination Team (RESPECT) in 2016, and the U.S.-Mexico Agreement in 2019, have demonstrated a willingness to cooperate bilaterally.15 Yet, all of these initiatives have focused on irregular migration without addressing access to regular pathways. The United States and Mexico must coordinate regionally to better encourage and manage regular migration. Given the increase in apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border and resulting policy tensions among the two countries, there is a pressing demand for an alternative system.

Regular Migration as a Substitute for Irregular Migration

Due to the aforementioned difficulties in obtaining accurate data, little causal analysis exists that evaluates the efficacy of regular pathways in reducing irregular migration. It is difficult to empirically attribute a change in the volume, timing, or composition of migration to a particular policy change; the correlation between policy and migration changes does not prove there is a causal link. There are a small number of rigorous empirical studies that cite additional interaction variables, such as socioeconomic conditions or changes in border enforcement, which further complicate the relationship.

Data and research design limitations mean that existing studies cannot properly test for substitution effects; as such, they may overestimate the effects of policies of migration patterns.16 This highlights the need for more empirically informed insights about the short- and long-term effects of migration policies, such as the H-2B visa, on separate migration categories, including irregular migration from specific municipalities of origin.

Bither and Ziebarth (2018) evaluate Germany's Western Balkans Regulation, which made work visas accessible to six countries in the region that had little chance of receiving asylum.17 The number of asylum applications from the Western Balkans dropped after the regulation was introduced, from 120,882 first-time asylum applications in 2015 to 10,915 in 2017. Meanwhile 117,123 work contracts for applicants from the Western Balkans were pre-approved. But the authors argue that while the correlation is evident, identifying the causal relationship is difficult. There were simultaneously a number of other policies introduced at the same time, including border restrictions, faster asylum processing times, and the closure of the irregular route. The authors did not attempt to identify a causal relationship.

Clemens and Gough (2018) evaluate the relationship perhaps most similar to that which is presented here.18 They argue that while there is little evidence that regular migration channels can directly substitute for irregular channels, the U.S.-Mexico example illustrates that, under demographic and economic pressure, substantial legal channels for economic migration are necessary to curb irregular migration. However, these legal labor mobility pathways only suppressed irregular migration when combined with robust enforcement efforts. The authors did not attempt to identify a causal relationship.

Gutierrez et al. (2016) compared statistical data from a number of sources including the US Immigration and Naturalization Service and the US Customs and Border Protection for the time period 1942 - 2015, to compare the number of temporary work visas issued to Mexicans by the US and the number of apprehensions of Mexicans who had migrated irregularly.19 There is some historical evidence that shows that changes in illegal flows mirrored the changes in apprehensions over the studied timeframe; comparing the number of temporary work visas and the number of apprehensions illustrates an inverse relationship, but the authors did not attempt to identify a causal relationship.

The inadequacy of regular pathways to fill the demand for migrant labor is a major factor driving irregular migration, but regular pathways tend to be more available for male workers than female workers. Women migrants with low levels of education tend to work in non-seasonal, non-temporary sectors such as care for children and the elderly. Consequently, female workers can be particularly vulnerable as these sectors lack regular pathways.20

More inventive research strategies are needed using a comparative case study approach to assess specific phenomena, and draw conclusions about what works and what does not in terms of policies to discourage irregular migration and encourage regular migration.21 It is a challenge for policymakers to encourage migrants to engage with regular rather than irregular pathways, as those migrating irregularly are often the most distant from government outreach. For example, migrants from Myanmar often migrate irregularly to Thailand due to porous borders. There exists a Memorandum of Understanding between the two countries, but many irregular migrants are unaware of this or consider it too expensive.22 Thus, targeted communication strategies are vital in implementation.

Regular Migration to Deter Irregular Migration from Central America

In light of the promise that regular pathways hold as an alternative to irregular migration, the Biden administration has issued nationality-specific allotments of the H-2B visa designated for nationals from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The H-2B program makes 66,000 visas available for employers every fiscal year; however, the U.S. government has often issued additional visas beyond this cap.23

Beginning in FY2017, there have been exemptions to the H-2B visa cap beyond the mandated 66,000 visas in response to high levels of employers' demand for the visa.24 Couched in special appropriations bills, these blanket exemptions to grant more than 66,000 visas attest to the H-2B program's importance in advancing U.S. economic interests in certain industries, such as landscaping, housekeeping, and amusement parks.

Then, beginning in FY2020, the Biden administration announced a nationality-specific visa allotment for employers hiring employees specifically from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. A total of 6,000 visas were designated for this purpose, with the caveat that if all visas were not issued by a certain date, the remaining amount would be returned to the general pool - those of which most often go toward employees from Mexico. This was partly motivated by the premise that expanding access to regular visas would reduce irregular migration from the three countries.

The H-2B nonagricultural seasonal visa allows U.S. employers to recruit noncitizen employees for up to three years, provided the employers cannot locate U.S.-based workers and employ their workers for a minimum number of hours. Given the high demand among employers for visas as issued under the nationality-specific allotments, the program's expansion could prove to be successful in substituting for irregular migration if implemented correctly.

Practical Challenges to Substitution of Irregular Migration

As the U.S. Government expands the H-2B program for individuals in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, it faces three primary challenges: coordinating with ministries in countries of origin, guaranteeing migrant workers' rights, and ensuring visa holders comply with return requirements.

There was some initial doubt among practitioners that these nationality-specific visas would even be used; decades of hiring through recruitment networks primarily in Mexico would make it seem feasibly impossible to quickly build strong, equivalent networks in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. For at least the past two decades, the majority of H-2B visas (74%) have been issued to workers from Mexico, followed by 10 percent from Jamaica, and just 3 percent from Guatemala.

FIGURE 3: Top Ten Countries of Origin for Recipients of H-2B Visas (stacked), 2014 - 2020

Contrary to initial doubts, the first special H-2B allotment, issued in the spring of 2020, was in overwhelming demand from employers - those who actually apply for the visa on behalf of potential employees.26 It is not publicly clear why the total 6,000 visas were not ultimately issued in time, but the Seasonal Employment Alliance attributes this confusion to a lack of coordination with Ministries of Labor in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras. It is critical that the participating governments communicate legal timelines to ensure that the visas allotted for each country are properly issued.

In addition to issues related to hiring individuals, the H-2B program also faces frequent violations of workers' rights. The H-2 program prohibits all entities involved in recruitment from charging migrants any fee, meaning that employers must cover all of the recruitment costs.27 Yet many have reported that illegal charging of fees during the recruitment process is a rampant problem, even among recruiters who may appear to be reputable.28 There is widespread agreement among practitioners that additional monitoring and regulation is needed to curtail this informal practice.29 Some private, ethical recruitment agencies, such as CIERTO Global and Stronger Together, operate in the region but their efforts primarily focus on Mexico and Guatemala. Expanding the market share of ethical recruitment organizations poses a challenge.

Finally, the H-2B program as a substitute for irregular migration may be threatened if visa holders want to reside permanently in the United States; the visas are temporary and currently do not offer "dual intent," or the possibility to later apply for permanent residency on the basis of being an H-2 visa holder. The H-2B program, as well as the H-2A program, have been successful in generating circular forms of migration from Mexico. The factors driving migration from Central America, however, range from persistent corruption and violence to protracted economic barriers that are not as widespread in Mexico.30 Visa overstay, or staying without proper legal status, may pose a challenge to the regular benefits of the H-2 program.31 However, current overstay rates for people from Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras with nonimmigrant visas are equivalent to those from other countries.32

The H-2B Program as a Component of Regional Cooperation on Managing Migration

The United States can implement policies to mitigate these challenges and improve the management of migration from Central America. Rather than simply focusing on changes to the U.S. immigration system, U.S. policy responses should pair these reforms with cooperation with the Guatemalan, Honduran, and Salvadoran governments to ensure these legal pathways address the scale and scope of irregular migration from the Northern Triangle in a sustainable way.

First, U.S. policymakers can create policies relating to logistics, labor law, recruitment certification, and returns to countries of origin. To expand the reach of the H-2B program while strengthening protections for workers, the following should be considered:

In the near-term, exemptions to the H-2B cap for people from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras should continue. This allows employers to hire more people from those three countries and creates a regular, accessible, and cheap alternative to migrating irregularly.33

Logistics. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services can also address financial and logistical costs by introducing temporary fee waivers for employers' or recruiters' air transportation costs, H-2B application forms, and consular processing. These measures could be phased out once employers create sustainable channels to hire workers from the region, which can be measured by a specified level of diversification among the nationalities of H-2B visa holders.

Labor law. The U.S. Department of Labor can require H-2 petitioning employers to submit evidence of ethical recruitment with each petition, similar to the requirements of a Labor Certification Application. Further, the agency could make regular consular visits to worksites compulsory, bar H-2 employers that have previously been on debarment lists, and require proof of compliance from any potential employee, ensuring that they will adhere to the validity period of their stay.

Recruitment certification. The U.S. Consulates could also make access to the H-2B cap-exempt visas contingent on the completion of a certification program that would certify that employers and recruiters engage in safe recruitment at the firm-level.34 Firms that successfully complete the certification process, which can also require compliance with regulations in the countries of origin, would be eligible for the cap exemption, as well as associated fee waivers.

Returns to Countries of Origin. The U.S. Agency for International Development can make important changes to ensure returns on development while visa holders are in their country of origin during the off-season. In coordination with U.S. Consulates, service providers can offer programming to visa holders that can serve to guarantee training or employment placement upon return, disseminate newly acquired human capital in municipalities of origin, and ensure that the benefits and rules of the program are properly communicated at the community level.

U.S. policymakers should also work with the labor and foreign ministries in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras to promote safe recruitment in countries of origin and compliance with labor law in the United States. Policy considerations include:

- The respective Ministries of Labor could report to the U.S. Department of Labor regarding the compliance of recruiters and employers with U.S. law and the laws in countries of origin.35 This reporting can help the U.S. agency determine employers' eligibility for the H-2B cap exempt visas, providing another layer of review to ensure employers are in compliance.

- The governments of the United States, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, as well as organizations such as the IOM and ILO, could provide comprehensive "know your rights" training to H-2 visa holders to ensure workers know which practices constitute legal violations.

- The U.S. Department of Labor could create a platform through which consular staff from the three countries can report labor concerns during regular visits to H-2B worksites in the United States,36 including a forum to share best practices with NGOs and other stakeholders.

Conclusion

This essay has shown how the H-2B program may offer a regular alternative to irregular migration. U.S. policymakers and their Central American counterparts are strongly considering this legal channel as they attempt to manage irregular migration from the region. While the United States often considers immigration solely as a domestic policy issue, the scope and complexity of the newest forms of irregular immigration vastly exceed the capacity of solely one government to address these challenges. Immigration is an intermestic policy area that requires regional and hemispheric cooperation.

The policies discussed herein pose several governance challenges, which the governments of the United States, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras have just begun to address. As these nationality-specific allotments continue to roll out, it will be vital that the responsible policymakers properly evaluate their programming. The implementation of nationality-specific labor visa allocations, if seeking to reduce irregular migration, should include a causal evaluation of irregular migration from the regions where H-2B visa holders originate. Evaluations of poverty impact from these temporary visas should also be considered; researchers at Stanford University have already begun such a study in Mexico.37 If policymakers would truly like to address the hemisphere's migration challenges, further research on legal pathways—and the impacts they had and will continue to have—must be considered. Only by clearly establishing the relationship between regular visas and irregular pathways can such policy discussions progress.

Footnotes

Download here.

Footnotes

Download footnotes here.