There are long-standing questions about the benefits and costs of international trade integration. An abundance of work has pointed to the economic benefits of integration, including productivity gains from the increased use of global value chains (GVCs). However, the Covid pandemic reignited fears that complex supply networks are also a source of macroeconomic volatility, and sparked calls to re-shore supply chains to improve macroeconomic resilience. In this piece, based on a broader analytical report (d’Aguanno et al. 2021), we revisit the productivity-volatility debate with relation to trade openness, focusing on GVCs. We show that the relationship between GVC integration and volatility is ambiguous in theory, and insignificant in the data. Moreover, we find that policies to re-shore production lead to an increase in aggregate volatility, as they effectively increase the concentration of value chains on domestic sources. On the other hand, diversification of GVCs among foreign suppliers can lower volatility, by reducing the exposure to any single country.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the institutions to which they belong.

Introduction

Since the end of World War II, countries have become highly interconnected through trade in goods and services, spurred by wide-ranging reductions in trade barriers. Global value chains (GVCs) have been a key component of trade integration, with economies becoming ever more reliant on one another for intermediate inputs. Today, around half of world trade is characterised by GVC trade (World Bank 2020).

Despite clear economic benefits of integration, some have argued that trade openness is a ‘double-edged sword’: while it can boost productivity, this might come at the expense of increased volatility. So the argument goes, integration can encourage specialisation and, thus, limit the degree of flexibility in the face of shocks (Newbery and Stiglitz 1984). In contrast, others have shown that by fostering diversification, openness can lower volatility by reducing exposure to domestic shocks (Caselli et al. 2020).

We assess the effect of trade openness on volatility when accounting for trade in inputs, and find limited evidence of a double-edged sword.

Global Value Chain Integration

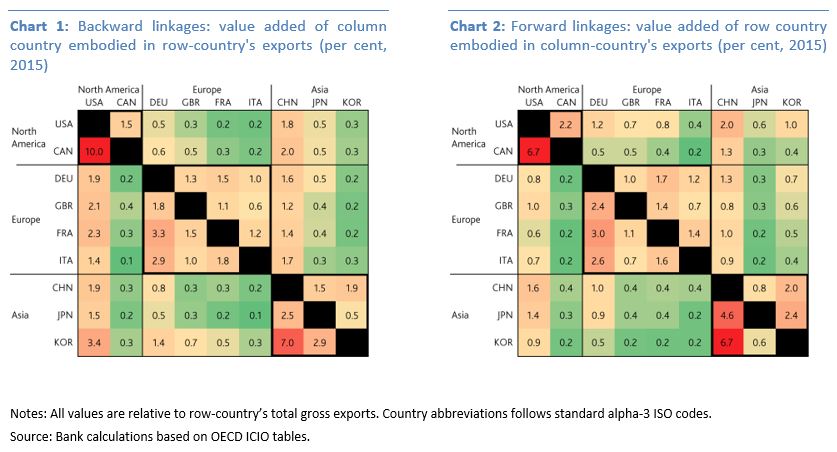

We use world input-output tables1 to calculate countries’ GVC integration as the sum of backward and forward linkages (BFL). Backward linkages capture the share of foreign value added in domestic gross exports, while forward linkages capture the domestic value added in foreign countries’ exports, relative to domestic gross exports.

To take a simplified version of perhaps the most widely used example, the iPhone is produced through a GVC: it is designed and marketed by the US firm Apple, but assembled in China using parts and components predominantly from Korea. Korea’s value added embodied in China’s exports of iPhones is a backward linkage for China. US exports of iPhones containing Chinese value added are a forward linkage for China.

Charts 1 and 2 plot bilateral backward and forward linkages in 2015 for all G7 members plus China and Korea—all key players in terms of their importance for GVC networks—broken down by bilateral trade partner. The colouring scheme is a heat map, where green, orange, and red values indicate small, moderate, and high linkages, respectively.

Two key messages emerge. First, China and the US are both major sources of value added used by other countries (Chart 1) as well as major users of value added generated by other countries (Chart 2), as shown by the orange-shaded columns for CHN and USA. Second, backward and forward linkages between regional partners are higher than across regions, as indicated by the orange and red cells inside the regional boxes for North America, Europe, and Asia.

Aggregating the BFL measure into a single country-level figure, we tease out four key determinants of a country’s GVC integration:

- Countries that have larger markets are less integrated into GVCs;

- Countries whose output is skewed towards manufacturing goods are more integrated into GVCs;

- Nearby trading partners are more integrated into each other’s GVCs; and

- Countries that face lower policy barriers to trade are more integrated into GVCs.

The dimension of GVC integration that is affected by policy decisions is the focus of a model, which we use to look at the theoretical relationship between openness, productivity and volatility.

Theoretical Model

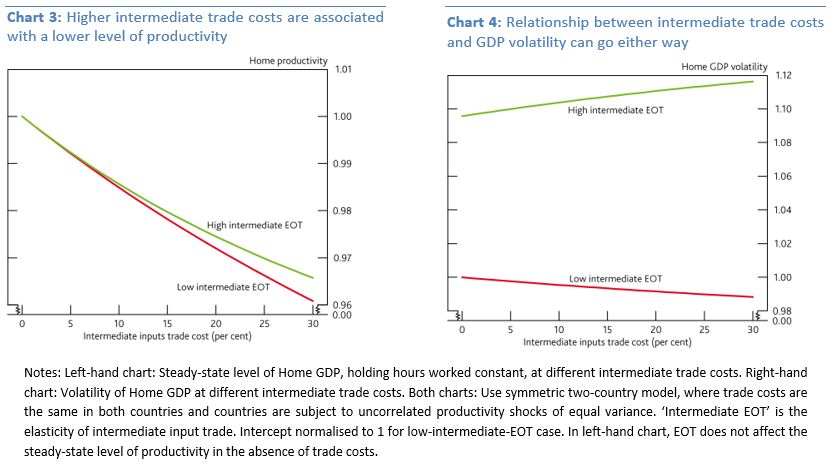

We set up a structural model to explore the theoretical relationship between trade barriers, productivity, and the volatility of income. The model has trade in final goods to reflect household consumption, and trade in intermediate inputs to reflect GVC trade. Lower barriers to input trade imply greater trade openness. The ‘elasticity of intermediates trade’ (EOT) is the key parameter that guides the extent to which firms substitute between Home and Foreign inputs.

Three key factors determine the degree of GVC integration in the model:

- GVC integration is increasing in the intermediate-input share – i.e when a larger share of gross output comes from domestic value added, there is less GVC integration;

- GVC integration is declining in the degree of ‘home bias’ in intermediate inputs – i.e. when more inputs are sourced from Home, there is less GVC integration; and

- GVC integration depends on trade policy, which we capture by introducing a trade cost on imports of foreign intermediates.

To assess the link between openness and the level of productivity, we compare overall productivity at different intermediate trade costs (Chart 3). Productivity is highest when trade costs are low and openness is high. This standard result is not surprising as trade costs limit the extent to which intermediate goods are efficiently allocated to production across countries, irrespective of the EOT.

The relationship between openness and the volatility of economic activity is less clear-cut (Chart 4). Under the assumption of uncorrelated productivity shocks of equal variance, GDP volatility is larger at the higher EOT, regardless of the trade cost. However, the slope of the line with respect to the trade cost has the opposite sign depending on the EOT; the double-edged sword only exists with low EOT.

In addition to this qualitative ambiguity, a series of robustness exercises (whereby economies experience correlated shocks, are more specialised, and differ in size) indicate that, where the double-edged sword does exist, the quantitative costs of openness in terms of volatility are small in comparison to the gains in terms of productivity.

Empirical Evidence

We next take our model to the data and investigate the double-edged sword empirically. Since productivity and volatility are determined by many factors beyond GVC integration, we use an econometric specification which relies on sector-level data and imposes stringent controls to tease out this relationship.

Specifically, since sectors differ greatly in their reliance on intermediates, we explore whether the effect of a country’s integration into GVCs depends on the input dependence of any given sector. To do so, we define groups for high versus low input-dependent sectors, and interact this variable with our country-level measure of BFL. Country and sector fixed-effects control for structural differences between countries and sectors.

Overall, results show that the productivity effects from GVC integration are most pronounced in highly input-dependent sectors. In contrast, results for volatility are statistically insignificant and economically small, suggesting that GVC integration does not have

Re-shoring versus Diversification

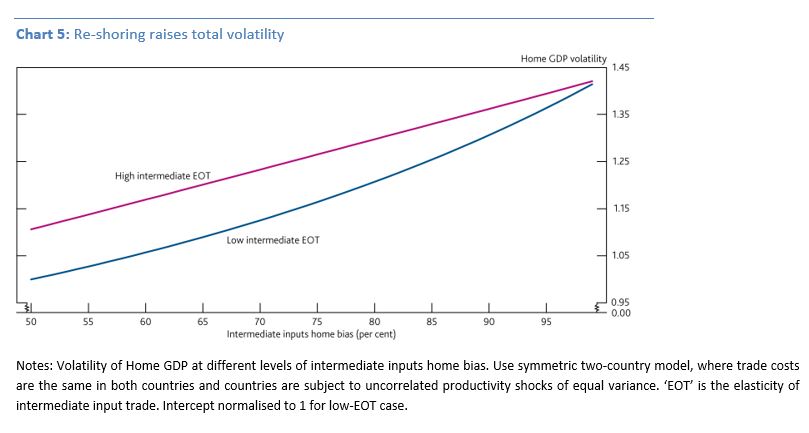

The Covid pandemic has re-invigorated the debate around the potential benefits of re-shoring supply chains—encouraging firms to source more inputs domestically—versus diversifying GVCs by encouraging firms to source inputs from more trading partners. We bring this debate to our model.

We show that increasing the share of domestically-sourced inputs raises aggregate volatility (Chart 5). Although greater self-reliance can reduce the influence of foreign shocks, it leaves firms less able to diversify the effects of domestic ones.

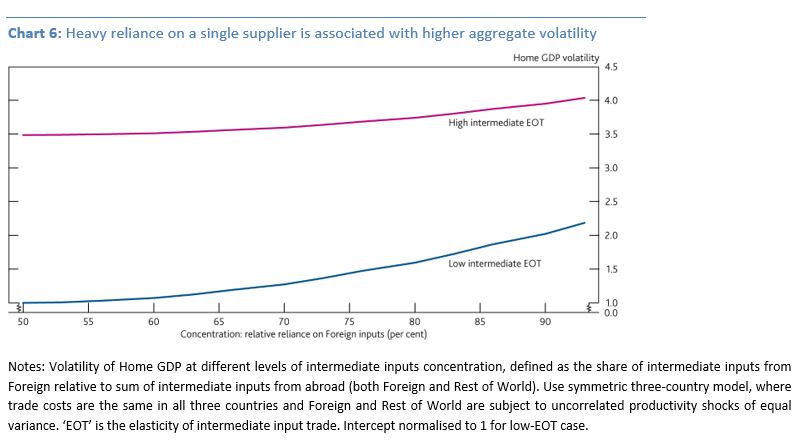

Similarly, when an economy has a high reliance on a single foreign supplier, its overall level of volatility is higher because the domestic economy is more exposed to shocks. Hence, diversified sourcing can lower volatility (Chart 6).

Of course, concentration risk may vary depending on countries’ top trading partner(s), due to the fact that some partners have more internal diversity in terms of exporting firms within an industry, or a more diverse industrial composition overall. Thus, some risks may be mitigated by diversifying suppliers within, in addition to across, countries.

"Safe Trade Openness" Debate

The recent pandemic has raised further questions about the safety of the global trading system, which extend beyond our analysis.

We argue that there is a good case for policy reforms in the global trading system, with similarities to the push for safe openness in the international financial system in the wake of the great financial crisis. The need for international co-operation was motivated by the complex, global nature of the financial system; this is no less true in the trading system. We propose three considerations:

- Strengthening existing frameworks that are in place to foster international cooperation on regulation and standards;

- Stress testing of global supply networks, in particular for critical sectors; and

- Enhanced collection and sharing of data on GVCs, to improve our understanding of where vulnerabilities lie.

Policy interventions, however, should only be considered in the case of well-identified market failures. Indeed, absent market failures, policy interventions may not be able to improve welfare relative to observed diversification patterns. More research is thus needed to explore potential information asymmetries, the concentration of GVCs, and the role of large firms. A clear diagnosis of such potential sources of inefficiencies is essential to devise welfare-improving policy interventions.

References

Caselli, F, Koren, M, Lisicky, M and Tenreyro, S (2020), ‘Diversification through trade’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(1), pages 449-502.

D’Aguanno, L, Davies, O, Dogan, A, Freeman, R, Lloyd, S P, Reinhardt, D, Sajedi, R and Zymek, R (2021), ‘Global value chains, volatility and safe openness: is trade a double-edged sword?’, Bank of England Financial Stability Paper, No. 46.

Newbery, D and Stiglitz, J E (1984), ‘Pareto inferior trade’, Review of Economic Studies, 51(1), pages 1-12.

Footnotes

1 World input-output tables show countries’ production in different sectors, as well as how much of it is sold as intermediate inputs (domestically and abroad) versus final goods and services (again at home and abroad).

About the Authors

Lucio D’Aguanno is an Economist in the Bank of England’s Global Analysis Division. He received his PhD in Economics from the University of Warwick.

Oliver Davies is an Economist in the Bank of England’s Global Analysis Division. He received Masters degrees in Central Banking & Finance from the University of Warwick and in International Development from the London School of Economics.

Aydan Dogan is a Research Economist in in the Bank of England’s Structural Economics Division. She received her PhD in Economics from the School of Economics, University of Kent.

Rebecca Freeman is a Research Economist in the Bank of England’s Global Analysis Division and a Trade Associate at the London School of Economics, Centre for Economics Performance. She received her PhD in Economics from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva in and her MA from Johns Hopkins SAIS.

Simon Lloyd is a Senior Research Economist in the Bank of England’s Global Analysis Division. He received his PhD in Economics from the University of Cambridge.

Dennis Reinhardt is a Research Advisor in the International Directorate of the Bank of England. He received his PhD in Economics from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva.

Rana Sajedi is a Senior Research Economist in the Bank of England’s Research Hub. She received her PhD in Economics from the European University Institute, Florence.

Robert Zymek is an Assistant Professor at Edinburgh University and an Economic Adviser in the Global Economics Team at HM Treasury. He received his PhD in Economics from the Universitat Pompeu Fabra.