A paradox in the global economic system is the case of Ethiopian agriculture and food security. How is it that a country that earns a bulk of their GDP from cultivating fertile land has a starving population? Despite the country's struggle with food, Ethiopia is displaying high growth numbers and is attracting considerable amounts of foreign direct investments1. This essay will explore the case of Ethiopian agriculture from three political-economic perspectives to evaluate agriculture-led growth. Is the agriculture-led development model a case of a successful or failed integration into the world market system? Or is it instead a case of neocolonial exploitation?

In the first chapter, I will briefly provide a historical overview of the current situation and highlight some of the challenges facing development in Ethiopia. The following chapter will outline a neoclassical view on the agriculture sector in Ethiopia, as well as highlight some issues with this approach. A subsequent chapter will explore a statist view on an agriculture-based developmental state, and why it is unlikely that Ethiopia will be able to follow the examples set by previous developmental states. Finally, the critical perspective will point out issues with both aforementioned

chapters.

Case – Land Investments in Ethiopia

In a 2009 report, Wageningen University and Research Centre, on behalf of the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, wrote:

It is concluded that the further development of the fruits and vegetable sector in Ethiopia for export to Europe and the Middle East has good perspectives and provides interesting opportunities for foreign investors. The sector is however still in its infant stage. Facilitating conditions for doing business are not yet optimal, but are expected to improve in the near future2.

This quote leaves us with a lot to unpack, especially with the political-economic perspectives in mind. To do this, we will begin by examining the state in which Ethiopia is today.

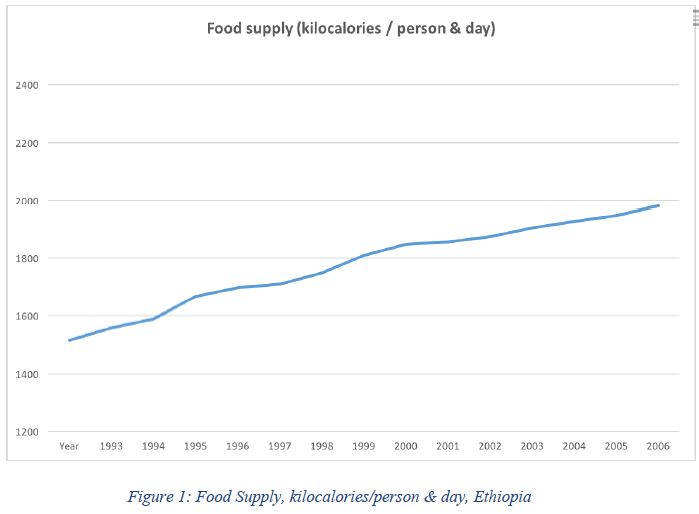

Between 1974 and 1991, Ethiopia was ruled by a Marxist military regime, under which agricultural land was state-owned and private ownership was limited. Hunger and famine led to many lives lost during this period; in response to one serious famine that claimed many lives in the early 1990s, the Marxist government enacted land liberalization. The same famine led to the creation of different armed resistance groups, united under the name Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), who took power in 1991 and further liberalized Ethiopia. A few more liberalizing reforms during the 1990s were enacted, causing overall crop yields to increase3. In Figure 1 below, data from the Global Hunger Index indicates that food supply per person in Ethiopia has steadily increased since these reforms4.

However, Ethiopia is to this day still ridden with famine and hunger. The 90s reforms were characterized by the usual neoliberal suspects: devaluing currency, enacting stronger property rights, opening up to international capital flows, and privatizing land and other state-owned enterprises.

Liberalization of Ethiopia led to a rush for land, which boomed after 2003. This trend began with foreign investors purchasing land in order to export flowers, mainly to Europe. In the years between 1995 and 2016, the ERDRF and subsequent governments transferred about 7 million hectares of land to foreign investors5.

Over the last decades, property rights have been strengthened, especially with regard to physical property6. Still, it would not be intellectually honest to call Ethiopia a place of extraordinary property rights, as it still ranks low in the Property Rights Index, at 108 out of 150 globally and 18 out of 26 in the region7. Remnants from the Marxist military regime still linger through multiple state-owned enterprises and land technically still owned by the government. The difference is that instead of the Ethiopian government being active in cultivating the land, they now grant leases to private investors deemed trustworthy. It is an outspoken priority for the Ethiopian government to attract foreign land investors and to ensure property rights for these investors by any means necessary.

Here it is important to mention the aspect of rural vs. urban groups in Ethiopia. Most of the so-called "land grabbing" has taken place in the southwestern regions of Ethiopia, where the dominant ethnic group is the Oromo people. A UK-based human rights group, the Oromo Support

Group (OSG), has estimated that over 4,000 people have been killed by government forces since 1994, but this is likely a very conservative estimate. Another approximation, which takes into account the scarcity of data, reaches well above 50,000 killings and disappearances between 1991 and 20168. The Oromo are mainly tribal farmers, and the area is home to two large national UNESCO World Heritage parks, which contain very fertile land sought after by international investors and Ethiopian state-run enterprises alike9. In the words of a local policeman, the government was "like a bulldozer, and anyone opposing its development projects [would] be crushed like a person standing in front of a bulldozer."10 As the analysis will show, this includes smaller native groups in other regions as well, such as the Anuak people in the Gambela area.

Further, it is important to distinguish between big agricultural capital and small-scale farmers in Ethiopia. First of all, Ethiopia has traditionally been a nation of farmers. Agriculture accounts for about 85% of employment and only 5% of total agricultural production comes from large commercial

farming. Most of what is produced by local small farmers is consumed directly by the household that produced it; only about a fifth of production is sold on the markets11. However, commercial agriculture is a growing part of the Ethiopian economy and the Ethiopian government plans to expand this sector, which will have important implications for small-scale farmers.

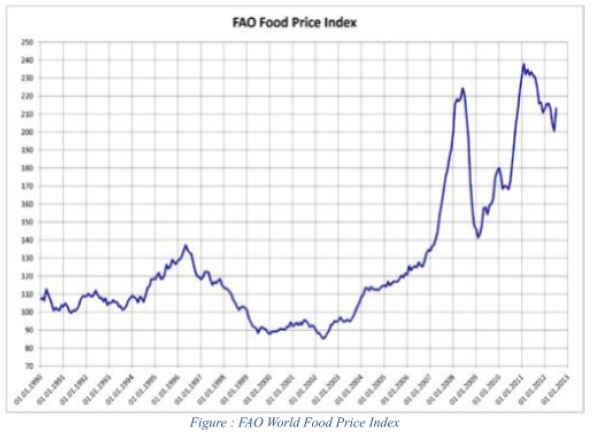

These small-scale farmers have been deeply affected by the global rush for agricultural investment, which began in the mid 2000s and continues today. This can be attributed in large part to sharp increases in food prices, which increased the return on investment for owning farmland, as the

graph below illustrates12.

Due to these price changes, financial investors began looking at cheap farmland in Ethiopia and in neighboring countries. This development led to what is dubbed the "landinvestment rush" by some and "land grabbing rush" by others13. To maintain a competitive edge, the Ethiopian government has been proactive in creating favorable investment conditions, such as very cheap land leases, tax holidays and exemption from royalties14. In cases where violence with previous cultivators of the land has been an issue, the government provides the investors with

military protection15.

Before moving on to our analysis of the land reforms from the three political economic perspectives, let us summarize where Ethiopia is today. Agriculture accounts for almost half of Ethiopia's GDP and about 80-90% of total exports16. Ethiopia has one of the world's fastest growing economies with a growth of about 8-15% annually. Some analysts argue that Ethiopia is Africa's strongest bid to become the "new China" in terms of being a factory for the world17. The services, transport and hospitality sectors account for about half of the current average 10.8% growth, mainly due to rapid urbanization. Even though agriculture is accountable for almost all exports, it is only responsible for 3.6% of the annual growth18. Moreover, this disconnect between agricultural exports and growth extends to disproportionate hunger levels in Ethiopia, with the World Food Programme estimating around 11.5 million people in need of emergency food aid19. In summary, there has been extensive land reform that has been driven by a will to attract foreign investors in the agricultural sector. This has been partly from within the state to combat food insecurity, but also influenced externally from increasing market values of food. With this in mind, we are going to apply three theoretical lenses to this case.

Neoclassical Perspective

Starting with an analysis from the neoclassical economist view, which is going to be the most positive perspective, we initially see some hopeful indications. The graphs since partial liberalization all show some positive correlation with regards to nutrition and economic growth, indicating that

hunger is solved through prosperity. This is in line with the goals of neoclassical economics, which is to maximize efficiency and value. Neoclassicists believe this is to be done through minimal government intervention and letting a free market decide where resources and capital should flow20. Eventually, this would lead to a convergence of economic output between the less developed nations and the most advanced economies21. Neoliberal theory acknowledges that former colonization is in part to blame for lagging growth and prosperity, but since the colonial age has officially ended, it should no longer obstruct a nation from enacting the right policies, such as strong property rights, and from minimizing government intervention in the economy, thus enabling growth22.

Speaking to this argument, we can see that when Ethiopia opened itself to trade and international capital, it did experience rapid growth in GDP, with capital flowing in from abroad and bringing efficiency to traditionally owned farms that had been working with very basic tools in an inefficient manner23. Since the previous farmland owners consumed most of what they produced, the gains from farming never translated into effects on GDP or exports. Once the farmland was leased to international and domestic investors, the products of which mostly went into exports, it provided the country with both income and wage employment. However, the market is far from free as land is still government owned.

A true neoclassical economist would point out that the violence in the Gambela region, where the government forcibly removed people from their land in order to lease it to foreign investors, was not the fault of the investors but of the Ethiopian government. In a free market society, the investors would have purchased the land from the small farmers instead. This would, in theory, lead to a situation where tribal groups like the Anuak would be compensated to the point where they were happy with the transaction and the deaths could have been avoided. This would require the land to have a selling price which the Anuak would be happy with and that matches a price the investors would want to pay. However, the Anuak tribe does not recognize individual ownership of land at all. Hypothetically, if half of the tribe agreed to a price and sold land to an investor, the other half would not recognize the arrangement, which could cause similar violence as already seen in the region24. If property rights were adequately enforced, it would mean the Anuak would not be driven away from their land, and therefore the subsistence agriculture of the tribe would continue to not add to the growth figures. This shows that the Neoclassical economics perspective has trouble dealing with cultural sensitivities.

Finally, let us return to the initial framework given for neoclassical economic arguments: the goals of maximization of value and efficiency. The spike of food prices in the mid 2000s and the proactive government policies in increasing competitiveness to attract foreign capital have successfully increased GDP growth in Ethiopia and converted non-profitable land (due to subsistence agriculture and inferior technology) into sources of profit. The investments come with employment opportunities, albeit with low wages, and, according to this perspective, these will lift Ethiopia out of poverty and hunger25. However, there are more things to consider than GDP growth, as the following arguments will show.

Statist Perspective

To some degree, the Ethiopian development model is state led because the land is owned by the state and leased to the companies who profit off of it. Compared to other examples of state-led development, most notably the East-Asian "Tigers", we see that some essential components are missing, which may highlight some issues with the agriculture-led development model. First of all, the basis of past state-led growth models have been to cap the amount of capital owned by foreign interests; none of the successful Asian countries have closed in on the traditionally wealthy countries by accepting large amounts of foreign capital. Conversely, they have made their own investments in both physical and human capital alongside an export-oriented growth policy26. If a country instead is dominated by foreign actors, it will usually be tormented by political instability and violence. Groups in the country wanting expropriation of resources and demands from investors to uphold unconditional property rights cause an incompatible divide between political groups. In the worst case, the country politically alternates between left and right wing revolutionary governments, all of them failing to improve the lives for citizens27.

The fact that 5% of agricultural output is produced by large capital investors, both domestic and foreign, suggests that Ethiopia is far from being dominated by these large investors. This is partly due to 35% of the leased land remaining underdeveloped as of 2016, which also has led the government to threaten to revoke the leases. In 2011, the government offered about 3 million hectares of land for foreign agriculture investors, of which 655,000 hectares were already leased28 29. Violence has already broken out over this relatively small amount of land, but the intent of the Ethiopian government to attract more foreign capital investments could lead to a point where the expropriation and displacement would cause a civil war30.

Secondly, in comparison to the East-Asian developmental states, the transfer of technological know-how to local farmers is low. The employees of the new big agriculture companies learn how to operate machinery, understand global market price setting and engage in more efficient business practices — all skills that would theoretically help Ethiopians set up their own businesses. An important difference is that people who would benefit from this knowledge are often the same people who were removed from the land in the first place, and the low wages they receive make it difficult to obtain new land and set up their own busines31. A statist would rather suggest that investments in land would have to be in cooperation with local farmers, and that capital transferred would have to be for the benefit of these locals. These investments would require motives other than maximizing profit, like the East-Asian developmental states who received foreign direct investments that were politically motivated32.

The Ethiopian agriculture industry can be characterized as an industry in its infant stage since a vast majority of the land is still used for subsistence agriculture. According to the statist perspective, the combination of infant stage industry and participation on the global markets will have negative long-run growth impacts33. The Ethiopian "productive power" in the agriculture sector is low, which would be the key issue for statists in this case. Previous developmental states focused on obtaining productive power in the technology sector, which is a path that Ethiopia does not necessarily have to follow. In theory, it could pursue being the world's supplier of food and coffee, for example. State investments in agricultural efficiency within Ethiopia to increase the output of each individual small farm will reduce the negative effects of bad harvests and drought, and thereby reduce hunger and famine.

Once the farmers are producing enough to feed Ethiopia itself, it can export the excess and have money flow into Ethiopia. Currently, a significant amount of food is exported but Ethiopia is continually running a trade deficit with its partners and, as previously stated, almost all of the exports come from agriculture. In fact, the trade deficit has only increased over the past 10 years34. Furthermore, the inflowing foreign capital might increase the levels of GDP growth, as it is technically part of the domestic production, but the investors who are benefiting from this growth are

not required to re-invest any of these earnings in Ethiopia itself. Instead, to ensure that the investors stay in the country, the government currently gives foreign investors tax breaks and exempts them from royalties35. So even though the country is showing impressive growth numbers, the benefits to the population remain questionable.

A more inclusive growth model based on agriculture would be to invest in domestic farmers. But, before the "land-grabbing" began, Ethiopia was one of the poorest countries in the world; thus, where would the required capital come from? The international donors that first pushed for reform

back in the 90s have since contributed a lot of money. One estimate cites that as much as $50 million has been donated to Ethiopian development36. The problem with old developmental state strategies is that they are no longer accepted according to international trade institutions and might lead to other donations from international institutions withdrawing from the development projects37. Another way of receiving donations could be by relying on the new Chinese development bank instead, which does not force neoliberal policy on its recipients. This is however a relatively new institution, so there is a chance that instead of neoliberal policies being pushed, other political pressure may follow.

Critical Perspective

Critical perspectives would agree with neoliberals that colonial institutions have traditionally been obstacles for development, but would go further and contend that the exploitative endeavors of colonialism did not end with the settlers giving up political rule in their former colonies. In critiquing neoliberalism, the critics might note that forcing former colonies to open themselves up to foreign capital and investors from richer countries is in itself neocolonial38. Consider the land-grabbing in the Gambela region: land from self-sufficient natives, who are not interested in partaking in the international global economic system, is taken by the government by force and expropriated. When met with resistance, the natives are detained and killed. Those who do not want to work for slave-like wages on the farms themselves are forcibly removed and put in "villages" constructed to concentrate people in a smaller area to access more land39. An account of this regarding the previously mentioned Anuak people is evidenced in the documentary Dead Donkeys Fear No Hyenas40. The statists might have a solution, which increases overall gains for the Ethiopian population, but the Anuak people would still have to comply with the development plan or be forcibly removed from their land. The source of frustration among the Anuak would still have to be addressed by the government in some way. Both the neoclassical and the statist models for development rely on exploitation because in both of these models, the natural resources would have to be taken by force.

The Ethiopian agricultural industry is technologically disadvantaged, not only when it comes to the production of food, but also when it comes to the storage of food. The frequent famines in the region imply a need for technological advancement, to make crops more weather secure and to help address the issue of food security in Ethiopia. What could the government do that does not involve exploitation? As we have seen, the tension between the Anuak and the government did not start with foreign direct investments but has a longer history. There are many more ethnic groups that have strenuous relations with both the government and other ethnic communities in the country. The amount of different ethnic groups in Ethiopia provides a challenge for development without any exploitation. In the era of Marxist military regime, cultural identities and languages were actively suppressed by the government. After the overthrow of the regime in 1991, the political system was changed to an ethnic federalism that allowed minority cultures to freely express themselves and have a degree of self-rule41. This would in theory minimize violence and exploitation between the groups. Yet, it still does not solve the question of how the more famine-prone regions would be able to survive. Since the various federations are all controlled by the same government, violent clashes between the ethnic groups happen continuously42. Furthermore, governmental interests are aligned with the interests of the foreign capital investors, against the less powerful farmers, who face the

choice of being either exploited, forcibly removed or killed.

This means that the power relationships in the land issues are in essence neo-colonial. The consequences of colonial investment-relations can be shown by examining past occurrences. In Latin America, for instance, similar structures of exploitation have been seen. In northeastern Brazil, massive investments in agriculture were made by Dutch colonizers and this area is now one of the poorest and most malnourished in the country, with land that is eroded and unfarmable, despite once being one of the most fertile areas in the region – not unlike the Gambela region in Ethiopia43. For Ethiopia to achieve long-term growth, it is imperative that the farming of the land is done in a way that considers long-term environmental effects of farming. A significant amount of fertile land is in the Gambela National Park, a largely forested area, and has to be cleared before it can be turned into crops. The region already suffers from degradation of land, water and forest, which has further increased food insecurity for the local communities44. This highlights the nature of foreign investment, which critical scholars would argue is continued colonial behavior and is killing parts of the population and extracting wealth out of Ethiopia for the primary benefit of western powers. The motive behind the investments are short-term profits, without land preservation or long-term sustainability in mind.

Conclusions

The Ethiopian model of development has proved to be a multilayered issue. Balancing the need for economic development, eliminating hunger and famine, complying with international policy, and minimizing violence between various ethnic groups seems to be an impossible task. But what can we conclude from examining the Ethiopian model of development? First of all, the current development does not seem to be sustainable in the long term. Particularly the "export food to import food"-model is alarming. Even with growing exports, the trade deficit continues to rise; there is capital flowing into Ethiopian agriculture and providing much needed modernization, yet the food produced is not for the benefit of the domestic population. Previously self-sufficient local farmers, who have not contributed to the impressive GDP growth-numbers, are now on UN food assistance.

So far, the evidence seems to point in a specific direction. The Ethiopian goal has been to produce food and obtain food security, while simultaneously achieving growth and prosperity. The route it has chosen looks mostly like the neoclassical route, by leasing land to capital-intensive investors to produce food while bringing in technology and know-how. However, food security seems to rest on a model that is not sustainable in the long term. The food that is produced with the new machinery and technology is exported to countries where the products fetch higher market prices while the government has to import food for its citizens. The trade deficit Ethiopia is running looks nothing like the previous East-Asian models of developmental states and will not be a sustainable model in the long run. The problem, regardless of perspective, is that it seems incompatible to gain the land necessary for food security while not forcefully displacing native cultivators of the land, which has already brought violence to the country. It is clear that any development model in the future needs to consider the native population as part of the way forward.

This argument is speculative but has support in academic literature45. Should this happen, any gains in food security and growth will be for naught and the consequences are yet incalculable. The statist perspective has shown that it would be possible to build a developmental state model based on agricultural exports, but it has to be led by the state, where priority would be to firstly provide existing small-scale farmers with the necessary tools and capital, to both increase crop yields and make production more weather secure, and secondly to provide food for the rest of the state. Once the Ethiopian agriculture sector reaches a high enough level of production power, it would theoretically be able to obtain growth numbers through export of this food while not losing income with the import of other food. Ideally, this would have to be done with the support and cooperation of local farmers, without displacement or political persecution. This is not without its share of problems, however. Both the ethnic conflict issue and the sourcing of capital provide two undeniable obstacles for implementing such a system.

Footnotes

1 A. Gray, Ethiopia Is Africa's Fastest-Growing Economy, 2018, link.

2 Wiersinga, R. C, & de Jager, A. Business opportunities in the Ethiopian fruit and vegetable sector. (Den Haag: LEI Wageningen UR. 2009), link.

3 J. Von Braun & T. Olofinbiyi "Famine and Food Insecurity in Ethiopia (7-4)." In Case Studies in Food Policy for Developing Countries: Domestic Policies for Markets, Production, and Environment , ed. P. Pinstrup-Andersen, & C. Fuzhi, (Cornell University Press 2009), link.

4 M. Lindgren, "Food Supply (Kilocalories / Person & Day).," Gapminder, October 12, 2010, link.

5 M Jaate, "Land Grabbing and Violations of Human Rights in Ethiopia.," Finfinne Tribune, January 28, 2016, link.

6 Property Rights Alliance, "International Property Rights Index.," International Property Rights Index., accessed

June 6, 2018, link.

7 Property Rights Alliance.

8 Jaate, "Land Grabbing and Violations of Human Rights in Ethiopia."

9 Survival International, "Ethiopia's 'Bulldozer' Government Arrests 100 Tribal People over Dam.," Survival International, October 16, 2011, link.

10 Survival International.

11 T. Burgis, "The Great Land Rush Ethiopia: The Billionaire's Farm.," Financial Times , March 1, 2016, link.

12 Jashuah, "FAO Food Price Index from January 1990 to July 2012.," (Wikipedia Commons., May 10, 2012), link.

13 Burgis, "The Great Land Rush Ethiopia: The Billionaire's Farm."

14 Burgis; N. Eyassu, "We Export Food to Import Food," Pambazuka News, April 20, 2011, link.

15 Jaate, "Land Grabbing and Violations of Human Rights in Ethiopia."

16 S. Anderson and E. Farmer, "USAID Office of Food for Peace - Food Security Country Framework for Ethiopia FY 2016 – FY 2020" (Washington, D.C: Food Economy Group, 2015), link.

17 D. Kopf, "The Story of Ethiopia's Incredible Economic Rise.," Quartz, October 26, 2017, link.

18 Kopf, "The Story of Ethiopia's Incredible Economic Rise."

19 World Food Programme, "Ethiopia," n.d., link.

20 R. Gilpin, Global Political Economy: Understanding the International Economic Order (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2011), 28–29.

21 G. Mankiw, Macroeconomics (Basingstoke: Worth Publishers, 2013), 240–41.

22 Mankiw, 247–48.

23 Burgis, "The Great Land Rush Ethiopia: The Billionaire's Farm."

24 Cultural Survival, "Anuak Displacement and Ethiopian Resettlement," Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine, December 1988, link.

25 Eyassu, "We Export Food to Import Food."

26 T. Piketty, Kapitalet i tjugoförsta århundradet , trans. Ohlsson L (Stockholm: Karneval Förlag, 2015), 78.

27 Piketty, 79.

28 T. Burgis, "Ethiopia Hands Dissident 9-Year Jail Term.," Financial Times, April 28, 2016,https://www.ft.com/content/81260aec-0cc2-11e6-ad80-67655613c2d6; T. Lavers, "'Land grab' as development strategy? The political economy of agricultural investment in Ethiopia.," Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 1 (2012): 114; W. Wallis, "Ethiopian Land Protests Put down with Deadly Force.," Financial Times , February 2016, https://www.ft.com/content/ca4ee89e-ce77-11e5-831d-09f7778e7377.

29 As of September 2018, Ethiopia suspended 95 leases and regained a total of 412 hectares of land, due to it being underdeveloped, as well because of protests linked to land grabs (Halake 2018). This paper was originally written in June 2018, so many assumptions on continued land grabs were taken for granted as the Ethiopian government had indicated to expand these programs at the time.

30 Wallis, "Ethiopian Land Protests Put down with Deadly Force."

31 Eyassu, "We Export Food to Import Food."

32 E. Thurbon and L. Weiss, "The Developmental State in the Late Twentieth Century," in Elgar Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Development, ed. E. Reinert, R. Kattel, and J. Ghosh (London: Edward Elgar, 2016), 640.

33 B. Selwyn, The Global Development Crisis (Cambrige: Polity Press, 2011), 34–35.

34 Trading Economics, "Ethiopia Balance of Trade," 2018, link.; Anderson and Farmer, "USAID Office of Food for Peace - Food Security Country Framework for Ethiopia FY 2016 – FY 2020."

35 Eyassu, "We Export Food to Import Food."

36 Jaate, "Land Grabbing and Violations of Human Rights in Ethiopia."

37 H.-J. Chang, Kicking Away the Ladder: Policies and Institutions for Economic Development in Historical

Perspective (London: Anthem Press, 2002), 2.

38 D. Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press Inc, 2005), 35, 56.

39 Burgis, "The Great Land Rush Ethiopia: The Billionaire's Farm."; Jaate, "Land Grabbing and Violations of Human Rights in Ethiopia."

40 J. Demner, Dead Donkeys Fear No Hyenas, Documentary (Malmö: WG Film, 2017).

41 E.J. Keller, "Ethnic Federalism, Fiscal reform, Development and Democracy in Ethiopia.," African Journal of Political Science 21, no. 50 (2002): 22, link.

42 T. Gardener, "Ethiopia's Tense Ethnic Federalism Is Being Tested Again.," Quartz , September 15, 2017, link.

43 E. Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America - Five Centuries Of The Pillage Of A Continent, trans. C. Belfrage (London: Monthly Review Press, 1973), 62ff.

44 A.W. Degife and W. Mauser, "Socio-economic and Environmental Impacts of Large-Scale Agricultural Investment in Gambella Region, Ethiopia.," Journal of US-China Public Administration 14, no. 4 (2017): 195, link.

45 Piketty, Kapitalet i tjugoförsta århundradet, 78–79.