The EU Taxonomy represents a defining inflection point in sustainable finance, transitioning the field from voluntary principles to a rules-based governance model. This article examines how Regulation (EU) 2020/852 has simultaneously reshaped European financial markets and emerged as a global reference point through the Brussels Effect. What makes the framework genuinely transformative is its dual capacity to function as both a binding EU regulation and a flexible global reference point, reconciling standardization with necessary contextual adaptation. While implementation remains uneven across sectors and firm sizes, the Taxonomy's science-based methodology has fundamentally altered how sustainable investments are identified and evaluated.

Introduction

The global financial landscape is increasingly shaped by the urgent need to address climate change and environmental degradation, leading to a surge in sustainable investment. At the forefront of this transformation, the European Union (EU) has introduced the EU Taxonomy for sustainable activities, a landmark regulation enacted through Regulation (EU) 2020/852. By establishing science-based criteria for six environmental objectives

1 - from climate mitigation to biodiversity protection - the European green classification provides the first standardized methodology to distinguish truly sustainable economic activities.

Beyond its regional impact, the framework exerts a global influence through what is known as the "Brussels Effect," promoting policy diffusion, as well as through corporate adoption, fostering market adaptation. The Brussels effect reflects the EU's ability to set international standards due to its significant market size and regulatory ambition, prompting jurisdictions and corporations worldwide to align with its criteria. As countries develop their own sustainable finance frameworks and global firms adapt to access European markets, the Taxonomy emerges as an important factor for aligning global finance with climate goals. The article submits that the EU's sustainable classification operates as a dual-force instrument: domestically, it reallocates capital through binding rules; internationally, it serves as a voluntary global benchmark. The exposition ultimately argues that the Taxonomy is a critical juncture in financial governance: one that balances regulatory ambition with implementation pragmatism.

The analysis proceeds in three parts. First, it traces the rulebook's evolution from conceptual foundations to technical implementation, revealing how it overcame early definitional ambiguities in sustainable finance. Second, the inquiry assesses the framework's market impacts in Europe, where adoption grows despite persistent sectoral disparities and SME challenges. Finally, the investigation examines the sustainability screening tool's transnational governance role, showing how the Taxonomy influences both policy frameworks and corporate behaviour.

The Evolution of Sustainable Finance: From Broad Sustainability Concepts to Technical Criteria

Sustainable finance has historically struggled with definitional ambiguity. Sandberg et al. (2008)2 highlighted that Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) lacked a uniform definition. Over a decade later, Strauß (2021)3 observed that debates on sustainable finance continued to suffer from a lack of clear consensus on this concept's meaning. In response, EU's environmental finance policy evolved gradually, at first emphasizing initiatives, which were market-led, such as voluntary reporting. In this regard, notable regulatory milestone was the 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive4 (NFRD). The directive required environmental and social disclosures from large corporations, though without detailed reporting frameworks. In the words of the NFRD5, the goal was to set "a clear course towards greater business transparency and accountability on social and environmental issues."

Post-2015 Paris Agreement, momentum grew. The EU launched the High-Level Expert Group on Sustainable Finance6 (HLEG) in 2016. Two years later, HLEG's final report, "Financing a Sustainable European Economy,7" recognised the role of sustainable finance in achieving Europe's energy and climate policy objectives. The report concluded that €170 billion in annual investments were needed for Europe's climate goals. Furthermore, the document urged implementing and maintaining a common taxonomy to provide clarity in sustainable finance.

The Technical Expert Group on Sustainable Finance8 (TEG) (2018–2020) then crafted the Taxonomy's technical backbone, transforming broad sustainability concepts into specific technical criteria. Notably, TEG's work was characterised by inclusive stakeholder engagement, which helped bridge scientific evaluation and political compromise. Discussions about natural gas and nuclear energy were especially challenging, revealing difficulties in creating politically acceptable regulations. For instance, Germany, Luxembourg, and Austria opposed the classification of nuclear energy as sustainable9.

The 2018 Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth10 shifted policy from principles to technical classification, outlining ten actions to redirect capital while ensuring stability. The legal culmination of this process, Regulation (EU) 2020/85211, formalised this by establishing the framework for determining if an economic activity is environmentally sustainable. Since the Taxonomy Regulation does not define technical screening criteria, the Commission has issued Delegated Acts (DA) to supplement it. Since then, several DA have been introduced and amended, including the Climate Delegated Act12 (CDA) (2021), the Complementary Climate Delegated Act13 (CCDA) (2022) covering nuclear and gas, and the Environmental Delegated Act14 (2023) addressing additional objectives.

These additions and amendments expand and refine the EU Taxonomy framework. As discussed earlier, policy stances about some types of energy are starkly divergent – e.g. as of 2023, Germany phased out nuclear power15, while in France there are 56 nuclear reactors16. In response to policy challenges, the Commission split the classification of energy carriers and productions in two. The CDA focuses on energy carriers and productions widely accepted as green; the CCDA – on nuclear power and natural gas. This decision exemplifies both the adaptable nature of the emerging set of legal documents, governing sustainable finance, as well as the challenges and inevitable complexity, inherent to this process.

Notably, the introduction of the European sustainability screening tool has not been without critics. Opponents highlight economic burdens and complexity, questioning its economic viability17 and market compatibility18. Are critics right?

The Taxonomy in Europe: Gradual Adoption, Uneven Impact

The European rules-based framework has sparked debate about its practical impact, raising a key issue: has it meaningfully redirected capital toward sustainability? The answer requires assessing the extent to which the framework has influenced Europe's financial markets and investment patterns. This analysis examines several important aspects of the classification system's market effects. First, the focus is on assessing market impacts. Next, it highlights the diverse experiences of market actors navigating its requirements. Lastly, the discussion assesses rulebook's position within Europe's sustainable finance landscape.

Market Impacts: Taxonomy-Aligned Investment, Revenue, and Sectoral Disparities

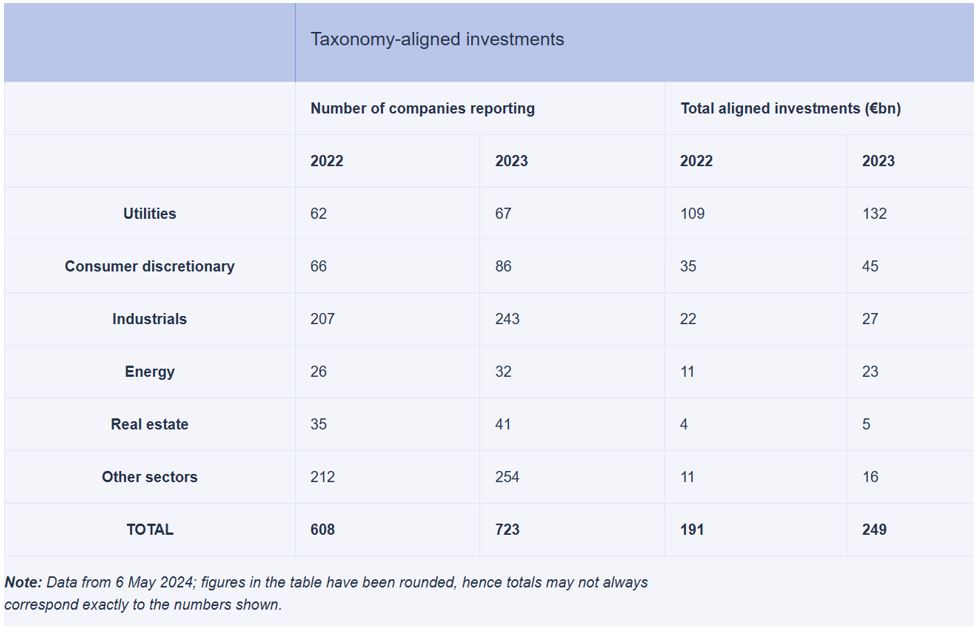

In Europe, evidence of market adaptation to the framework is emerging, as shown in data about Taxonomy-compliant investments from the European Commission (2024)19 presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sectoral Distribution of EU Taxonomy-Aligned Investments (2022-2023).

(source: European Commission, 202420)

The data highlights the increasing adoption of Taxonomy-conforming investments across various sectors between 2022 and 2023. The total number of companies reporting such investments rose from 608 to 723, while total aligned investments grew from €191 billion to €249 billion, about 30.4% increase. This trend could be interpreted as early evidence of the institutional uptake of sustainable finance criteria. However, a more granular sectoral look at the data, subject to limitations due to data availability, provides both context and nuance to this initial observation.

Before proceeding with analysis, it is important to acknowledge data constraints and potential confounding factors affecting the assessment of Taxonomy-compliant investments across all sectors. Comprehensive 2022-2023 data on total investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation, GFCF) and firm counts are unavailable in Eurostat's structural business statistics, which provide such data only up to 2020. For sectors like consumer discretionary and utilities, estimating total investment would require excessive approximations due to the lack of recent, sector-specific GFCF data, precluding their inclusion in detailed investment comparisons. For other sectors, this analysis relies on proxy measures, such as R&D investment for industrials (data for 2022 and 2023 is provided by the EU Industrial R&D Investment Scoreboard for 202321 and 202422, respectively), International Energy Agency (IEA) estimates for energy, and CBRE data for real estate to contextualize total investment trends23. This study therefore adopts a descriptive approach, using growth rates and shares, while acknowledging the limitations of proxies and data gaps24. Sectors are discussed following Table 1's presentation to ensure consistency with the primary data source.

While the upward trend of Taxonomy-aligned investment shows momentum overall, closer examination reveals that the European sustainability screening tool is influencing markets unevenly across sectors.

Utilities and Consumer Discretionary: Taxonomy-congruent investments grew by 21.20% (€109 billion to €132 billion) for utilities and 28.57% (€35 billion to €45 billion) for consumer discretionary. Direct comparison with total investment trends is limited by data availability, though growth indicates increasing Taxonomy compliance.

Industrials: Using EU R&D investment as a proxy25, total R&D investment grew by 7.3% (€219.2 billion to €235.2 billion)26 while Taxonomy-conforming investments increased by 22.73% (€22 billion to €27 billion). Keeping in mind that R&D is not a direct proxy for total industrial investment, this comparison shows that Taxonomy-aligned investments grew faster than EU R&D, suggesting stronger growth in sustainability-focused investments. Energy: Taxonomy-adherent investments more than doubled from €11 billion to €23 billion (109% increase). During this period, total EU investment in renewables generation grew by only 4% (€98 billion to €102 billion)27. The share of aligned investments in total renewables investment thus nearly doubled from 11.22% to 22.55%, indicating accelerated integration of sustainability standards.

Real Estate: Taxonomy-conforming investments increased by 25% (€4 billion to €5 billion) amid a market contraction where total European real estate investment fell from €305 billion28 (2022) to €158.62 billion29 (2023). The share of aligned investments grew from 1.31% to 3.15%, suggesting prioritization of compliance by some firms (likely larger ones) despite challenging market conditions. However, low absolute figures indicate persistent barriers for many firms, particularly smaller ones.

Overall, the steady expansion of Taxonomy-aligned investments and rising number of reporting companies signal improved transparency. However, sectoral variations highlight challenges to uniform application. Energy shows stronger alignment growth, likely due to clearer pathways for renewable projects.

According to the EU Platform on Sustainable Finance (2025), Taxonomy-compliant revenue across reporting entities grew by 22% (€670 billion to €814 billion)30, lagging behind the 30% rise in aligned investments. This suggests a delay between capital deployment and financial returns. The European Investment Bank (2023)31 attributes this to structural barriers: market prices often fail to capture the full benefits of sustainable projects, compounded by high initial costs and extended payback periods. These trends indicate the regulatory framework is promoting institutional investment in sustainable activities, but alignment remains modest and sectorally-uneven, necessitating further data for robust analysis.

The market impacts analysis reveals a mixed picture: while Taxonomy-compliant investments and revenue are growing, sectoral disparities underscore challenges in achieving uniform adoption and varying pathways to sustainability. These market dynamics shape the experiences of market actors navigating the rulebook's requirements.

The Compliance Spectrum: Contrasts in Market Implementation

To illustrate the EU Taxonomy's diverse market impacts, this analysis examines two contrasting stakeholders. The first one is BNP Paribas - a global bank leading in sustainable financing. The second one is European Small and Medium Enterprises (SME), with a particular focus on those in Germany, Europe's economic anchor and home to a dense and influential SME sector. These cases reflect the spectrum of market actors navigating the classification system's requirements: from well-resourced large institutions to under-supported smaller firms.

BNP Paribas' reputation for financial resilience, innovation, and commitment to sustainability offers unique insights into global financial markets and sustainable finance. The bank's commitment to Carbon neutrality has increased its focus on sustainable financing . In 2021, it established the Low-Carbon Transition Group33 of over 250 experts to support clients on sustainable financing. By September 2022, the bank's lending to low-carbon energy projects exceeded by 20% its fossil fuel ones34. Part of this strong performance reflects the structural advantage enjoyed by large banks under the EU Taxonomy. Due to current eligibility definitions, financing extended to corporates is typically considered eligible, while loans to SMEs are not35. As a result, banks with corporate-heavy portfolios, like BNP Paribas, report higher alignment than those serving predominantly SMEs.

In contrast, SMEs highlight the Taxonomy's challenges, noting its complexity and resource demands as barriers to adoption. A 2023 Eurochambers36 survey found that the EU's sustainable finance framework has unintentionally imposed considerable administrative obligations on European SMEs, while yielding limited financial benefits. According to Eurochambers37, large corporations easily obtain sustainable funding from capital markets. At the same time, SMEs encounter persistent obstacles in securing comparable financing. Reporting and compliance requirements are widely seen as disproportionately burdensome for European SMEs38.

Even in Germany, Europe's leading economy, SMEs struggle to align with the Taxonomy's technical screening criteria, due to limited resources for reporting and verification. German industry associations and SME representatives have argued that EU sustainability regulations, including the Taxonomy, are often modelled on the conditions of large companies39. Thus, they fail to consider the limited budgets and staffing of SMEs40. Many German SMEs are concerned that the increasing bureaucratic demands of sustainable finance regulations could overstretch their capacities41. Some of them describe the new rules as a potential "bureaucratic monster" for smaller firms42. Surveys show that sustainability reporting remains a "black box" for many SMEs, and the lack of expertise and resources hinders their ability to comply43.

The struggles of German SMEs illustrate why the Taxonomy's European adoption remains incremental. While large corporations like BNP Paribas leverage the framework for competitive advantage, SMEs are often locked out by its complexity. Until policy tools address these disparities (e.g., via simplified criteria for small firms), market transformation may remain incomplete.

Progress and Potential Within Europe's Sustainable Finance Ecosystem

While the EU Taxonomy represents a regulatory inflection point in sustainable finance governance, its transformative impact on markets is ongoing. The rulebook introduces unprecedented technical precision and clearer standards, yet its reach within Europe's sustainable finance universe is still evolving toward comprehensive coverage.

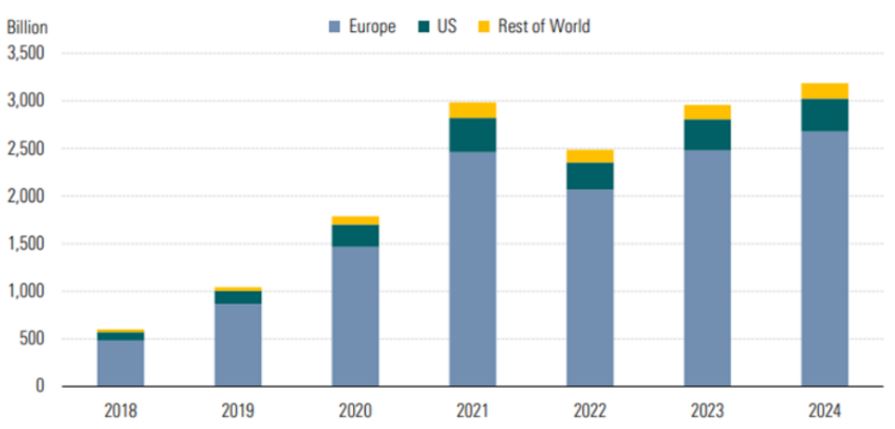

Morningstar (2025)44 reports the broader market for sustainable investments across regions, including Europe, where diverse regulatory frameworks coexist (see Figure 1).

According to the data, global sustainable fund assets reached USD 3.2 trillion by the end of 2024, with Europe holding USD 2.7 trillion. Within this context, Taxonomy-adherent investments represent an important and growing subset of Europe's sustainable assets. This pattern highlights the framework's current position as the vanguard of a broader transformation rather than a fully implemented standard. The green classification enhances transparency and comparability for a significant segment of the market. However, many investments still operate under less stringent or alternative classifications as they navigate the transition toward full alignment.

Figure 1. Sustainable Fund Assets in 2024. (source: Morningstar, 202545)

The gap between total sustainable assets and Taxonomy-compliant investments does not contradict the framework's influence but rather illustrates the scale of transformation underway. As the subsequent section demonstrates, the Taxonomy's impact extends far beyond its direct application, through its role in shaping global standards and corporate behaviour worldwide.

The Taxonomy in Europe

The evidence presented in these subsections reveals the sustainability screening tool's transformative, yet still-developing impact on European financial markets. Overall, the EU green classification has successfully established a science-based framework that enhances comparability and disclosure. It has also set new standards that are increasingly influencing global sustainable finance practice. There is meaningful growth in Taxonomy-conforming investments and revenue, reflecting progress in market adoption and transparency. However, the sectoral disparities indicate that implementation remains uneven, with some sectors adapting more quickly than others. This nuanced picture suggests that, while the rulebook represents a genuine inflection point in the evolution of sustainable finance, market participants require time to fully adapt to its requirements. Having examined these implementation dynamics within Europe, the analysis now turns to how the EU sustainability framework exerts influence beyond EU.

The Taxonomy's Global Influence: Between Policy Diffusion and Market Adaptation

The EU Taxonomy represents a novel form of transnational governance in sustainable finance. This section argues that the European green classification operates as a binding regulatory tool within the EU. However, its extraterritorial influence relies largely on voluntary standard-setting, a distinction that helps explain its uneven global uptake. An argument is made that the classification system exerts global influence through two interdependent mechanisms: (1) policy diffusion via the Brussels Effect, and (2) market adaptation through corporate and institutional adoption. The resulting interplay between regulatory prescription and market-led adaptation forms a central theme in contemporary sustainable finance debates, as explored below.

Policy Diffusion through the Brussels Effect

The sustainability screening tool's global impact is most visible in its role as a regulatory template. While the EU enforces compliance domestically, non-EU jurisdictions selectively adapt its principles. According to the EU Platform on Sustainable Finance, over 58 taxonomies globally have been influenced by the EU's approach46. Countries as diverse as China, Canada, and the UK are developing their own sustainable finance taxonomies, which have been influenced by the EU model47. This regulatory ripple effect exemplifies the "Brussels Effect," where EU standards shape practices far beyond Europe. Importantly, this global influence is more about standard-setting and policy modelling than direct implementation. Countries adapt the EU framework to their specific economic contexts rather than adopting it wholesale.

A notable example of this influence is the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT), developed by the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF)48. The CGT is a comparative study of China's Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue (referred to as the "China Taxonomy") and the EU Taxonomy's Climate Delegated Act49. Published on November 4, 2021, at COP26, the CGT aims to identify areas of convergence and divergence between the two frameworks and could serve as a basis for a global standard for sustainable finance50. While not legally binding, the CGT enhances clarity and transparency for cross-border sustainable finance. It also serves as a reference for taxonomy development in other regions. For instance, Hong Kong has expressed its intention to use the CGT as a reference for designing its own sustainable finance taxonomy, further illustrating the EU Taxonomy's global reach51. Singapore's Green Finance Industry Taskforce (GFIT) published its taxonomy consultation paper in 202252. The paper explicitly references the EU Taxonomy as a benchmark, while adapting principles to suit the ASEAN region's transition needs53. These adaptations demonstrate how the EU framework serves as a foundation that other jurisdictions modify according to their economic structures and transition pathways.

Market Adaptation: Corporate and Institutional Adoption

While the EU sustainability framework's policy diffusion reshapes national frameworks, its market adaptation operates through corporate and institutional channels, each responding to the framework's pull in distinct ways. Multinationals, ratings agencies, and asset managers increasingly engage with the framework: whether to comply, compete, or critique.

Multinational corporations are increasingly aligning their sustainability practices with the EU Taxonomy to meet investor expectations and maintain access to the EU market. Under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD)54, large EU-based companies with over 500 employees, €40 million in turnover, or €20 million in assets are required to disclose their alignment with the EU Taxonomy, starting from fiscal year 2024. This requirement will be with phased in to include smaller firms and listed SMEs by 2026. Non-EU firms with significant EU operations, generating over €150 million annually in the EU and having at least one subsidiary or branch, are also subject to the CSRD's third-country reporting requirements55. This has prompted many such firms to begin aligning with the EU Taxonomy standard. Non-EU firms with EU-based investors now also face growing pressure to report their alignment with the Taxonomy56, even if their home jurisdictions lack equivalent rules.

For instance, HSBC, one of the world's largest banks with €3.04 trillion in assets as of 200357, has integrated the EU Taxonomy into various aspects of its operations and financial products58. HSBC's alignment with the Taxonomy is both a compliance requirement (under CSRD) and a strategic imperative to attract EU capital.

This de facto globalization of the Taxonomy reflects the 'Brussels Effect' in action.

Ratings agencies such as MSCI ESG Research LLC, Refinitiv, and V.E (part of Moody's ESG Solutions) have incorporated EU Taxonomy alignment into their environmental (E) scoring methodologies, evaluating companies' contributions to sustainable activities like climate change mitigation59 . However, this relation is not significant for S&P Global's E ratings60, indicating that the EU Taxonomy's potential to reduce divergence in ESG ratings has not yet been fully realized.

BlackRock Investment Management (BlackRock), the world's largest asset manager has been notably ambivalent. Its position mirrors an ongoing debate within the sustainable finance community about how to balance environmental objectives with practical market realities. The firm has openly criticized the framework61, yet it simultaneously emphasizes the importance of climate-related risks in its investment strategies, revealing a layered perspective. In 2024, BlackRock Inc. allocated $150 billion to funds assessed for energy transition risks and opportunities62. Moreover, while reportedly these funds are primarily based in Europe, the new guidelines may also impact BlackRock's US-based funds63. However, in 2025 the firm exited the Net Zero Asset Managers (NZAM) initiative, a global coalition committed to net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or earlier64. Still, BlackRock has affirmed that it will continue to evaluate significant climate-related risks, suggesting a commitment to sustainability that diverges from outright dismissal65.

The allocation of $150bn to Taxonomy-influenced funds reflects the framework's gravitational pull, even as the firm critiques the rulebook. This paradox underscores the sustainable finance classification's role as an inflection point: its standards are now unavoidable reference points, even for reluctant adopters. However, BlackRock's exit from the NZAM initiative suggests that the financial industry's alignment with the sustainability screening tool, and sustainable finance generally, remains a contested, evolving process. The firm's ambivalence epitomizes the European green framework's paradoxical impact: even as it becomes a global reference point, its implementation remains contested. This tension underscores the framework's unresolved trajectory, a theme explored in the conclusion.

Conclusion: A Turning Point in Sustainable Finance Governance

The EU Taxonomy represents a decisive shift in sustainable finance, establishing the first comprehensive classification system for science-based classification of environmentally sustainable activities. Its development from conceptual principles to operational criteria marks a critical juncture in financial governance, creating new pathways for capital allocation while revealing persistent implementation challenges.

Within Europe, adoption continues to grow but remains uneven across sectors and firm sizes, reflecting tensions between regulatory ambition and market realities. Future policy refinements, particularly SME-focused adjustments and sector-specific guidance, could accelerate implementation. Globally, the EU green classification's influence as a regulatory prototype demonstrates the "Brussels Effect" in its contemporary form: not through uniform adoption, but via adaptive emulation by jurisdictions and corporations navigating sustainability transitions. This diffusion mechanism underscores the sustainability framework's paradoxical nature: it is simultaneously a mandatory compliance framework within Europe and a voluntary reference point globally.

The Taxonomy's ultimate significance may lie not in its current adoption metrics, but in establishing that financial systems can - and must - be systematically realigned with environmental imperatives. While challenges of complexity and compatibility persist, the framework has irrevocably altered sustainable finance by proving that science-based capital allocation is operationally feasible. As this realignment continues to unfold, the EU green classification serves as both a benchmark and a catalyst for the next generation of sustainable finance.

About the Author

Dr. Radostina Schivatcheva holds a PhD in Development Studies from the University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. She also has an MA in International Relations from Cambridge and completed a Business Studies programme at the Cambridge Judge Business School. Her professional experience includes work at the London School of Economics' International Inequalities Institute, the EU Resource Efficiency Coordination Action, EURECA (Horizon 2020) project of the European Commission (EC), and participation in several EC COST Actions (FP1106, FP0801, CA22122 – current member). Her interdisciplinary research spans sustainable finance and global governance, situated at the intersection of development studies and international political economy.

Footnotes

Download footnotes here.