Belarus's relationship with Russia since the fall of the Soviet Union has been characterized by political and economic dependence. This paper examines the impact that international sanctions, imposed on Belarus in the wake of recent political unrest and Russia's war on Ukraine, are making on the dynamics between the two countries. Using the example of the potash industry, this paper argues that Belarus's dependence on Russia is exacerbated by the particular characteristics of Belarusian state-owned enterprises (SOEs), largely targeted by sanctions, and the outsized role they play in the Belarusian economy. The crippling impact of sanctions has had the unintended consequence of bringing the two countries closer together and has highlighted the fragility of the Belarusian economy and its overdependence on Russia.

Russia-Belarus relations: a brief history

Relations between the two neighbors have been cyclical in nature, characterized by periods of conflict and reconciliation. Belarus joined the Russia-led Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) in December 1991, the same year that the Soviet Union collapsed. The two countries grew closer after Alexander Lukashenko's ascent to power in 1994 and formed a supranational "Union State of Russia and Belarus" in 1996. Upon becoming president in 1999, Vladimir Putin pursued even closer relations with Belarus in a bid to strengthen regional hegemony—even proposing the absorption of Belarus into the Russian Federation, which Belarus resisted. This policy shifted in the 2000s when Russia sought to alleviate the economic burden of supporting the Belarusian regime and cut its energy subsidies to Belarus in 2007.1 Trade and border disputes characterized the two countries' relations in the 2010s, followed by a reconciliation motivated by Belarus's large debt to Russia and Lukashenko's need for global allies following the internationally unrecognized 2020 presidential elections.2

In terms of economic relations, Belarus is highly dependent on its neighbor. Belarus continued to benefit from preferential access to the Russian market following the fall of the Soviet Union. It had a substantial industrial base and an established export activity (in 1990, Belarus's total exports to GDP ratio in 1990 was at 50%, whereas that of Lithuania amounted to 37%, Ukraine to 30% and Russia to 28%), albeit of low-value added products.3 Total bilateral trade between the two countries reached $40.1 billion in 2021.4 Russia is currently Belarus's largest trade partner, receiving 45.6% of Belarusian exports in 2020. The balance of trade is heavily tipped towards Russia, which sent only 4.77% of its total exports to Belarus in 2020.5 Russia is also Belarus's largest creditor, having granted $106 billion in debt to Belarus between 2005 and 2015 alone.6

Belarusian SOEs' outsized role

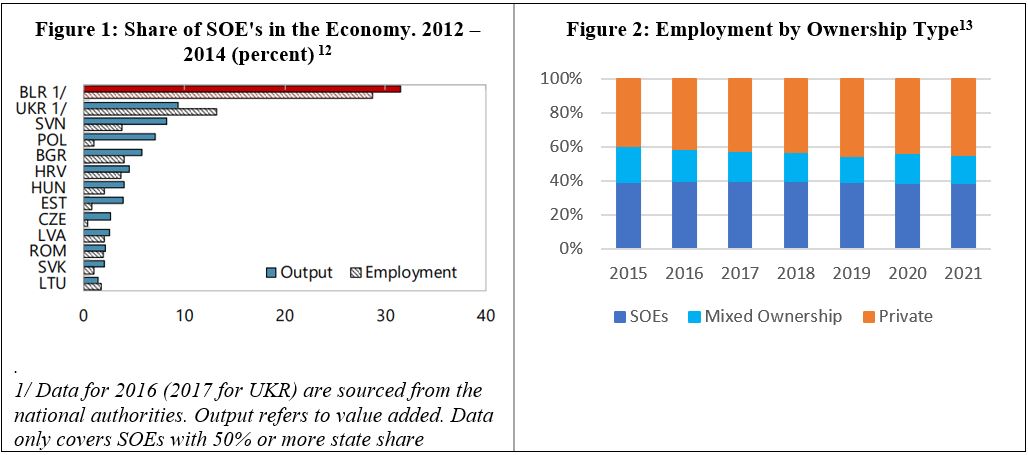

To understand how sanctions on Belarusian SOEs are increasing the country's dependence on Russia, this paper first examines the role of SOEs in the Belarusian economy. Belarus' economy is still characterized by a "dominant role of the state in economic decision-making."7 Unlike most other post-communist countries in the 1990s, Belarus preserved the state's role in economic activity, merging more successful SOEs with less profitable ones.8 SOEs are a major actor in economic activity: as Figure 1 shows, SOEs accounted for over 30% of value-added outputs in 2002 – 2004, much higher than neighboring countries.9 They also accounted for 63.7% of the total volume of industrial production in 2021.10 Employment can be seen in pure and mixed-ownership SOEs, though declining slightly over the past few years, still hovered around 55% of total employment in 2021 (Figure 2). The share of employment in the private sector is among the lowest in the region.11

Not all SOEs are created equal

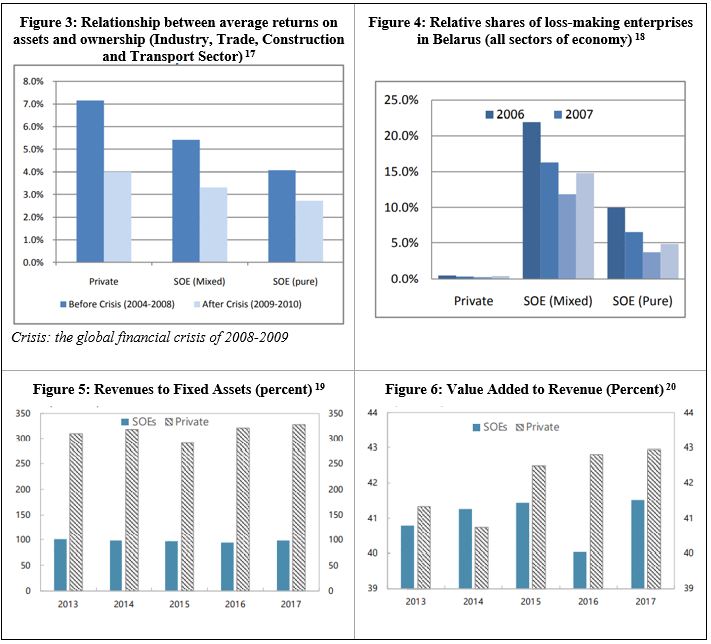

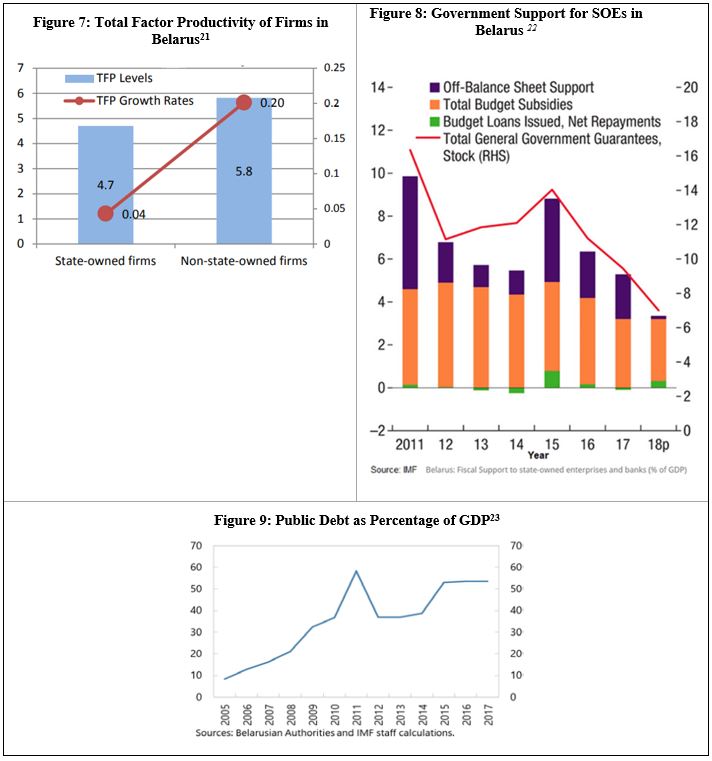

Belarusian SOEs vary greatly in their health and performance. Many of them have experienced declining performance over the past decade. The advantage they once held early in the post-Soviet era is being eroded by a combination of increases in labor and energy costs, slow technological upgrades, and heightened demand in traditional export markets for more sophisticated products.14 Average returns on assets and ownerships of Belarusian firms correlate inversely with their levels of state ownership. Relative shares of loss-making enterprises are 10-20 times higher for firms with partial or full state ownership (Figures 3 and 4). The ratios of firm revenue to fixed assets and value added to revenue can be significantly higher in privately-owned firms than in SOEs (Figures 5 and 6). There is a productivity disparity between private firms and SOEs, as evidenced by total factor productivity (TFP): not only do Belarusian SOEs have lower total TFP than private sector firms, their TFP also grows at a lower rate (Figure 7). An estimated one fourth of SOEs were making losses in 2015.15 At the same time, the Belarusian government continued pumping funds into struggling SOEs. The overall cost of this state support to SOEs amounted to 9.5% of GDP in 2015 (though some forms of it have declined since) (Figure 8).16 This support is largely financed by debt, which is steadily rising and has reached over 50% of GDP in 2017 (Figure 9).

There are multiple reasons for this weak performance. Belarusian SOEs suffer from the so-called principal-agent and free rider problems that plague firms with dispersed (as opposed to concentrated) ownership, be they publicly or privately owned.24 The Belarusian government has established data reporting mechanisms to monitor the financial situation of SOEs better. This system currently covers over 500 enterprises owned at the national level. It could be further strengthened and expanded to cover regional government-owned SOEs.25 Another issue are soft budget constraints, which stem from SOE access to extra-budgetary government support.26 Belarusian SOEs are increasingly able to secure additional financing from state-owned banks and stave off the threat of bankruptcy (Figure 8) in addition to other forms of government support.27 Finally, as is typical for SOEs, Belarusian SOEs are tasked with the objective of acting as a social safety net. This is evident from their high share of total employment compared to private firms, coupled with low TFP discussed above. SOEs in Belarus have rigid employment targets that hamper their ability to adjust to market forces, thus negatively impacting their performance and necessitating their dependence on government support.28

On the other hand, a number of highly profitable SOEs – active in areas such as defense, technology, finance, transportation and mining – constitute vital financing sources for the Belarusian regime. The Belarusian government requests additional payments from these SOEs and accumulates these payments in a "national development fund" created in 2005. The list of SOEs that are asked to contribute, as well as the amounts appropriated, are based on the SOEs' yearly results. In 2020, 40 entities were identified as payers to the national fund. In December 2022 a presidential decree expanded the list of payers to include subsidiaries established by SOEs, starting January 1, 2023.29

Sanctions and Belarusian SOEs

Belarusian SOEs have been hard-hit by the successive waves of international economic sanctions imposed by the US, EU, UK, Canada, and Australia, among others. These sanctions came in response to the Belarusian state's human rights abuses, weaponization of migrants crossing its territory into Europe, and ties with Putin's regime. New rounds of sanctions have been imposed on Belarus in the past year over its support for Russia's war on Ukraine, which began in February 2022. These sanctions restrict the exports and economic operations of specific Belarusian SOEs in sectors such as defense, finance, and transportation, or SOEs that constitute a source of revenue for the regime. Sanctions also impose unfavorable terms of trade on Belarusian companies, including SOEs, both generally and in specific sectors. These include restrictions on the import and export activities of certain products with Belarus and the revocation of most-favored nation (MFN) status under the World Trade Organization (WTO), resulting in the imposition of high import tariffs on Belarusian products.30

Economy-Wide Impact

The disruptions caused by the war on Ukraine and the ensuing intensification of international sanctions have greatly affected the Belarusian economy. In the period January to May 2022 Belarus's exports dropped by 4.2% year-on-year, to $17.4 billion.31 According to Belarus's Prime Minister Roman Golovchenko, by the month of May, Western sanctions had blocked $16 - $18 billion worth of Belarus' exports in 2022, which accounted for "almost all of Belarus's exports to the European Union and North America."32 Despite the rise in petrochemical product prices, Belarus's top export, Belarusian oil refineries are struggling after losing one of their biggest markets, Ukraine, as well as major export routes through neighboring countries. Foreign reserves are expected to contract. In 2022, Belarus's GDP is estimated to have dropped by 7% while the inflation rate reached 19%.33 The government has even made increases in consumer prices illegal in an effort to tame inflation.34

The Belarusian Potash Industry

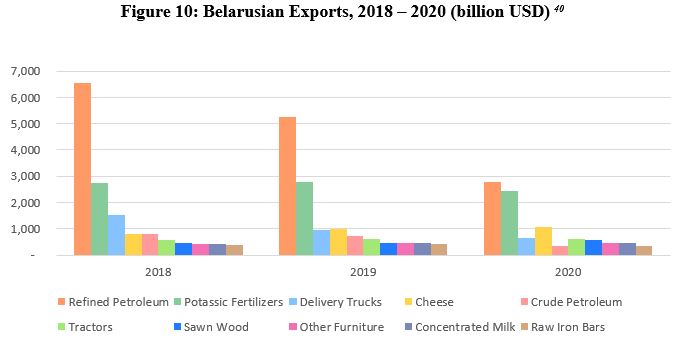

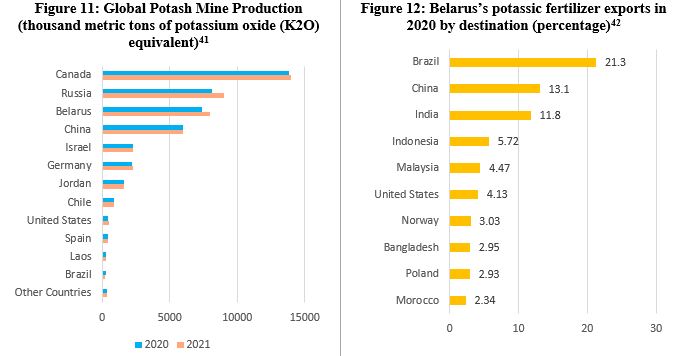

The sanctions imposed on the potash sector can help explain the impact of sanctions on Belarusian SOEs and the ripple effect on the Belarusian economy as a whole. With $2.44 billion, potassic fertilizers (potash) constituted 8.7% of Belarus's total exports in 2020, second only to exports of refined petroleum, as demonstrated in Figure 10.35 As Figure 11 shows, Belarus is the world's third producer of potash, after Canada and Russia.36 With about 10-12 million metric tons of potash exported annually, Belarus provides around a fifth of the world's total potash exports.37 The largest buyer of Belarusian potash is Brazil, followed by China and India. Figure 12 shows Belarusian fertilizer exports by destination. Fertilizers, including potassic fertilizers, are key inputs in major commodity crops such as corn and soybeans. Russia and Belarus together account for 38% of global potassic fertilizer exports, 17% of compound fertilizers, and 15% of nitrogenous fertilizers.38 The sanctions imposed on Russia and Belarus have contributed to fertilizer shortages and price increases, with serious implications for global food security. Fertilizer scarcity could eventually lead to a reduction in their use, which would further reduce agricultural yields and production, fueling more food price increases.39

The main entity exploiting Belarusian potash reserves is Belaruskali, one of the largest producers of potash fertilizer in the world and one of the largest SOEs in Belarus. The Belarusian Potash Company (BPC) – the country's sole potash exporter – handles the trading and exportation of potash for Belaruskali. BPC is partially owned by Belaruskali, among other SOEs. The Belarusian potash industry has been heavily targeted by sanctions and trade restrictions, as it is highly state-controlled and helps finance the Belarusian regime. The industry provides the Belarusian government with tax revenues, as well as foreign currency through exports. In 2020 BPC was also the top contributing SOE to the national development fund.43

Trade restrictions by the EU were first imposed on Belaruskali on June 24, 2021. The US, UK and Canada introduced restrictions on August 9, 2021, and again on December 2, 2021. No restrictions were imposed on the Belarusian Potash Company (BPC) at the time, allowing Belarus to continue to export potash, albeit at lower volumes as many buyers turned to other sources to mitigate uncertainty.44 Sanctions on Russian and Belarusian potash contributed to price hikes which initially compensated for the decreasing export volumes. BPC finally received US sanctions in December 2021, along with BPC subsidiary Agrorozkvit, as well as Slavkali, which produces potash fertilizers and was constructing a large mining facility in Belarus.45 Total or partial bans on doing business with Belaruskali, BPC, and other potash-related SOEs, as well as restrictions against the imports of Belarusian potash products, were greatly ramped up since the start of Russia's war against Ukraine. For example, the EU sanctions package introduced on June 3, 2022 included direct bans on Belaruskali and BPC, adding to the existing restrictions on the import of Belarusian potash fertilizers into the bloc.

These sanctions and related financial and logistical restrictions are proving to be devastating to the Belarusian potash sector, even though the bulk of Belarus's potash exports goes to third-party countries. Landlocked Belarus shipped virtually all of its potash exports north through Lithuania to the port of Klaipėda on the Baltic Sea. However, on February 1, in response to international sanctions, Lithuania terminated the contract between Lithuanian Railways (LTG) and Belaruskali for the transit of potash through Lithuanian territories to Klaipėda.46 Ukrainian Railways (Ukrzaliznytsia) had also suspended Belarusian potash shipments through Ukraine's territory to the port of Odessa shortly before the start of the war.47

Belarus is already struggling to supply its top potash buyers. Brazil has had to cancel its imports from Belarus and is now looking to develop its own potash reserves to mitigate uncertainty.48 Canada's share in Brazil's fertilizer imports increased from 31% in 2021 to 37% in 2022.49 China indicated that it had sufficient domestic stocks to sustain fertilizer production and stop potash imports for the time being.50 Plans for Indian importers to pay Belaruskali in rubles through Russian banks have fallen through due to sanctions on Russian financial institutions.51 By April, India had already secured potash deals with Canada, Israel and Jordan to compensate for the loss of Russian and Belarusian potash.52 It is thus unsurprising that Belaruskali declared force majeure on February 16 and announced that it was no longer able to meet its contracts.53 It has been reported that, by March 21, three out of Belaruskali's five mines had stopped production due to the unavailability of export routes and that the company had to take out loans to pay its employees' salaries.54 In the meantime, to respond to global fertilizer demand, other global potash exporters, such as Canada's BHP and Nutrien, are contemplating or even planning on raising their production.55

Russia and Belarus had been discussing the shipping of Belarusian potash through Russian territories and ports. However, Russian ports such as Ust-Luga on the Baltic Sea are already near capacity with Russian products and would not be able to handle the large volumes of Belarusian potash exports. Moreover, transit routes from Belarusian mines and factories to Russian ports are currently inadequate. Sizeable investments over extended periods of time in both routes and ports would be needed.56 On February 18, 2022, Putin gave instructions to build a terminal near St. Petersburg to accommodate Belarusian exports restricted from transit through neighboring countries due to sanctions.57 By the end of June the construction of a Belarusian transshipping port in Bronka, southwest of St. Petersburg, was underway.58 In September 2022, Belarus signed an agreement to build a new terminal in the Russian Murmansk port on the Barents Sea.59

Belarus has dropped its potash prices to 60% lower than potash from Russia and Canada. Due to the hike in global potash prices Belarus should still make a profit margin.60 However, even if the investments needed in ports and routes were undertaken to export Belarusian potash through Russia, the increased transportation costs through the more distant Russian ports would raise the cost of potash for Belarus and diminish profit margins. Investing in a Russian route for Belarusian potash may ultimately be futile as buyers could turn to other potash sources by the time these investments are completed.61

How sanctions are affecting relations with Russia

Even though Belarus may have wished for greater independence from Russia before the war, international sanctions are bringing the two countries even closer together, on both economic and political fronts, while deepening Belarus's dependence on its larger, more powerful ally. The particular characteristics of Belarusian SOEs have played a non-negligible role in shaping Belarus-Russia relations under sanctions. Before the sanctions, cheap loans extended by Russia had helped Belarus support its failing SOEs, while its successful ones had provided enough funds to help the Belarusian regime maintain a certain degree of economic independence from Russia. With even the most successful SOEs (like those in the potash sector) struggling under the weight of sanctions, this balance has been disrupted.

Belarus is increasingly looking for Russia's support on the economic front, which Russia is happy to give considering its dearth of other close regional allies. In June, 2022, Russia backed Belarus in its discussions with the EU to establish a corridor through Belarus for Ukrainian grain to be exported through the Baltic ports. Russia declared that it would allow the transit of grain out of Ukraine to alleviate global shortages, in exchange for the EU lifting sanctions on Belarusian companies and allowing Belarus to resume exporting its petroleum and potash products out of the same Baltic ports.62 Belarus renewed this offer to the United Nations in December 2022, though both offers were refused.63 In March 2022, Russia also deferred its ally's state loans (which make up more than 50% of Belarusian state debt) for 5-6 years, thus easing the strain on the Belarusian economy caused by sanctions.64

Belarus has set its sights even higher. Western firms are leaving Russia and Belarus is hoping to fill the void by exporting its mechanical engineering, food, and other products to mitigate the sanctions' negative impact on exports.65 The Russian Prime Minister declared on June 22 that "Russia will do everything necessary to strengthen industrial cooperation with Belarus." The two countries are looking at developing transport infrastructure and import substitution activities.66 Belarus and Russia have created several new joint committees and a new government agency aimed at increasing bilateral trade to make up for lost exports of sanctioned products.67 Russian and Belarusian companies are also working together to get around the imposed sanctions. Belarus is intensifying weapon sales to Russia to offset the sanctions imposed on its military industry. Since the onset of sanctions in 2020 Belarus has been trying to substitute imports of Western components by ramping up joint R&D with Russian defense firms.68 Belarus is also hoping that Russia could buy some of Belarus's potash for domestic use while exporting more of its own potash.69

In return, Lukashenko has repeatedly affirmed his full support to Russia's military campaign against Ukraine. Since the beginning of the war, Belarus has permitted Russian troops to attack Ukraine from Belarusian territory,70 and is conducting military drills on the Ukrainian border.71 There has been speculation as to whether Belarus would become directly involved in the conflict, even though the regime's line so far is that it would only join the fight if Ukraine attacked Belarusian territory.72 A few days after the war started, however, Belarus held a referendum that dropped a neutrality clause from Belarusian constitution, meaning that Russia could deploy warfare capabilities (intelligence and electronic warfare, ballistic missiles, and even nuclear weapons) on Belarusian soil.73

Talks of strengthening the Union State of Russia and Belarus have been revived following the start of the war against Ukraine. On July 1, Putin said that Western sanctions are accelerating Belarusian-Russian unification, which serves "to minimize the damage from illegal sanctions, to make it simpler to master the output of required products, to develop new competencies, [and] to expand cooperation with friendly countries."74 The Belarusian Prime Minister stated in June that Western sanctions are driving Russia and Belarus closer together, "not only about manufacturing cooperation but also cultural, humanitarian, financial, and banking integration."75

The fate of continued Belarusian potash exports may lie in Russia's hands. Unlike Belarus's primary export of petroleum products, which depends on imports of Russian crude oil, Belarusian potash has, thus far, not depended on Russian support. However, Belarus's plan to export its potash through Russian ports, even constructing its own terminals within these ports, is contingent on Russian backing. Putin made a public show of support by saying in March of 2022 that additional ports on the Baltic Sea were important not only for Belarus, but also for Russia.76 Moreover, the proposals to create a Ukrainian grain corridor through Belarus in exchange for lifting sanctions, though unsuccessful, hinged on Russia's backing and acceptance to let Ukrainian grain leave the country. Had the grain corridor proposals been approved, they may have rendered Belarus even more reliant on Russia.

However, the extent to which Belarus can expect aid from Russia in reality may be limited. In 2020, potash and oil products were the biggest Belarusian exports by far, accounting for almost 20% of total exports. The complementary volumes of potash needed by the Russian market would not be sufficient to resolve Belarus's potash situation. In addition, developing exports to Russia in other industries will not be enough to compensate for the losses in petroleum and potash exports. Russia has been implementing its own import substitution programs, and the size of the Russian economy is expected to contract by 8.8-12.4% in 2022, two factors which may limit the market share that Belarusian companies can claim in Russia.77 Belarus's shrinking economy and reliance on the Russian market may expose it to further vulnerability.78 Moreover, Russia's support to Belarus could be limited by Belarus's unwillingness to acquiesce to engaging in full-fledged military action in Ukraine alongside Russia. Belarus is aware of this predicament and is trying to balance its dependence on Russia by pivoting towards other countries such as China and other friendly economies to the east and south.79

Conclusion

With international sanctions tightening around the Belarusian economy, the regime is paying a steep price for its alliance with Russia and support for Putin's war against Ukraine. However, instead of deterring Belarus's support to Russia, the war and sanctions are exacerbating Belarus's dependence on its bigger and more powerful ally. The particularities of Belarusian SOEs, their outsized role in the economy, and the great extent to which they have been impacted by international sanctions, are playing a role in limiting Belarus's options when it comes to engaging with Russia. This is highlighted by the example of the potash sector, which went from a considerable source of independent financing for the Belarusian regime to, instead, another contributing factor towards its close alliance with Russia.

Now that the two countries are largely isolated from the rest of the world, they will need each other's backing more than ever. Russia will utilize the current situation to keep Belarus close. Belarus is important for Putin's war on Ukraine, as it is strategically located between the two countries. Russia's support helps prop up the Belarusian regime, especially in the wake of the 2020 elections extending Lukashenko's rule. It also helps keep the economy afloat, especially in light of diminishing SOE revenues following sanctions. Belarus has so far resisted Russia's calls to engage in its war on Ukraine. Turning towards other friendly partners may help Belarus mitigate its dependence on Russia, but achieving this pivot will take time and may yield uncertain results.

About the author

Lina Sawaqed is a doctoral candidate in the Doctor of International Affairs (DIA) program at the Johns Hopkins University's School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS). She has also been working as a Private Sector Specialist at the World Bank for over 13 years, focusing on private sector development and foreign direct investment (FDI) in Africa, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. Prior to joining the World Bank, Lina worked with the Jordanian Embassy in Washington D.C. and with the Jordanian Government in Amman, mainly on FDI strategies and promotion. Lina holds a master's degree in International Business Management from the University of Provence in France and a bachelor's degree in Modern Languages from the Yarmouk University in Jordan. She speaks Arabic, English, French, Italian and Spanish.

Footnotes

Download footnotes here.